Kanye’s music has always reflected his inner thoughts.

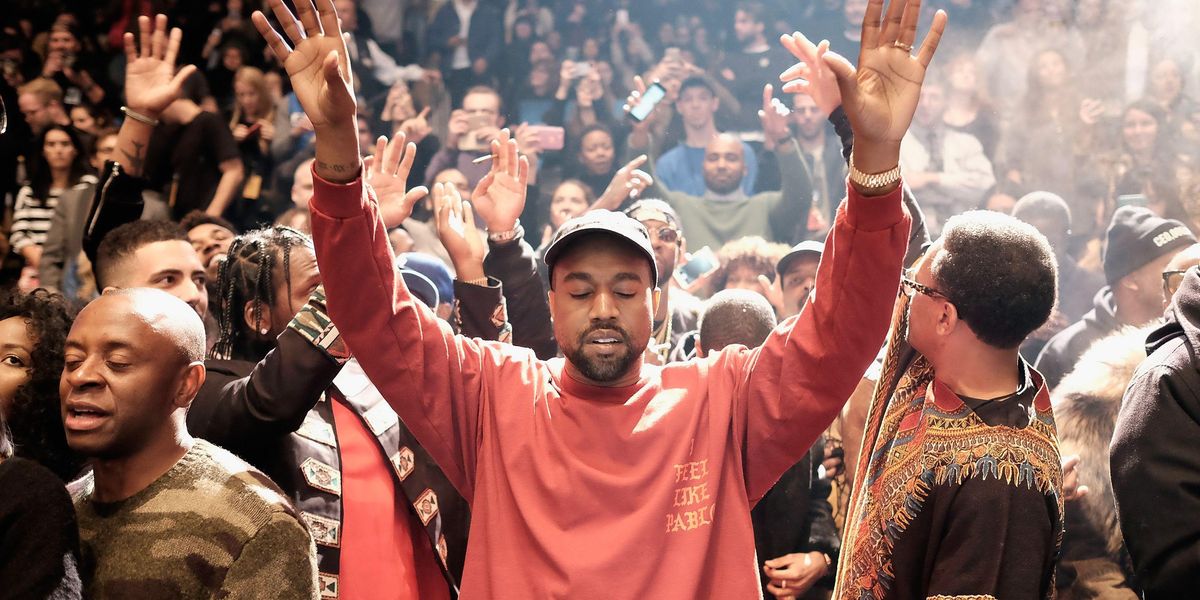

When Kanye released his seventh studio album, The Life of Pablo, on February 14th in 2016, we should have known things were about to take a turn for the worse.

The album, in short, was not Kanye’s best. There were some bangers. Its opening track, “Ultralight Beam,” was a Chance the Rapper gospel track introduced by audio from a viral video, so obviously that has stood the test of time. But the album did not live up to the epic emotion of its opening track. Not even a little bit.

The Life of Pablo received mostly positive reviews from critics for its experimental production and the fragmented style that has now become ubiquitous in Kanye’s work. It was also nominated for five Grammys, including Best Rap Album (which went to Chance the Rapper’s Coloring Book), but notably was not nominated for Album of the Year (which was ultimately given to Adele’s 25 over Beyonce’s Lemonade in a famous upset that surprised even Adele herself).

Despite its large critical acclaim and major streaming success, fans wondered where the old Kanye was. The new album was too fractured to have massive singles and lacked the commercial hits of his previous albums.

Notably, it also lacked the passionate emotional energy that had come to characterize and iconize West. From the grief and heartbreak that made him sing — and that would ultimately pioneer the tone of mainstream rap music that would set the stage for Drake and The Weeknd’s massive success — in 2008’s 808s and Heartbreak; or the passionate and unbridled energy of the bold and racially charged Yeezus, Kanye had become an iconoclast in rap for how much of his personality he put into his music. The Life of Pablo felt stale in comparison, its themes dry and derivative.

Pitchfork called it “the first Kanye West album that’s just an album: No major statements, no reinventions, no zeitgeist wheelie-popping. It’s probably his first full-length that won’t activate a new sleeper cell of 17-year-old would-be rappers and artists,” mostly because there’s not much to take from it. The non-linear, experimental style would be done insurmountably better by Frank Ocean’s Endless and Blonde later that same year, and its meditations on life were meditations on Kanye’s life — and the rest of us, his audience lest he forget, are not Kanye.

The Life of Pablo is a case study on fame, faith, and family. The album sees Kanye lamenting about fake friends, greedy family members, and the downsides of his massive success. However, these are not new themes, neither unique to Kanye or to his music.

In his critically acclaimed My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, Kanye approached the perils of fame with more nuance and vitality. MBDTF was a masterclass in production and thematic vision, creating a cohesive album that felt constantly innovative without feeling scattered. Uniquely in that project, Kanye balanced his braggadocious self-congratulations with the acknowledgment that he had become an undeniable mainstay in the rap game. There, in his peak and prime, his ego felt earned. From “Runaway’s” production and visuals that proved he was a multi-talented artist not just a rapper, to Nicki’s verse on “Monster” — which showcased his propensity for mentoring and catapulting artists to mainstream fame — Kanye gave a career-defining performance on that album that far surpasses the lackluster effort on Pablo.

Kanye West – Runaway (Full-length Film)

www.youtube.com

Both albums have similar preoccupations, but on Pablo they have evolved and become fixations. Who could forget the Grammy-winning “All of the Lights,” a Rihanna and Kid Cudi-backed feast of sound, complete with those iconic strings, and its lyrics about balancing his personal life and his celebrity? And how could “Real Friends” and “Famous,” which are ostensibly about the same concerns, ever compare?

They don’t. In Pablo, Kanye is mostly concerned with his perceived persecution as an artist and using his music to retaliate or start drama. “Real Friends” feels less like transcendent social commentary than a rant about his personal grievances, and “Famous” was the product of controversy for his line about Taylor Swift — “I feel like me and Taylor might still have sex / I made that b*tch famous.”

The ensuing drama with Taylor devolved into a circus of regression that was reflected in both of their music. Taylor’s next album, Reputation, was a pointed attack at West, and West was busy lighting flames to the fire of his relationships with everyone, including long time collaborator Jay Z.

For a while, it was entertaining, but now the reckless and self absorbed behavior that accompanied Pablo has come to characterize Kanye West. In the song “I Love Kanye,” he rapped “I miss the old Kanye” in an ironic dismissal of all the fans who wanted him to stay the same. At the time, this seemed tongue and cheek. Now, I can’t help but listen to it in earnest.

But here’s the thing: the old Kanye is the new Kanye. Though they seem unrecognizable, the Kanye who said “George Bush hates Black people” is still obsessed with being controversial and counterculture — but the culture has changed so Kanye has gone the opposite way to meet it from the other side. The Kanye that wrote “Jesus Walks” is the same Kanye that started Sunday Service and made Jesus is King — but where religion had first been a grounding force of humility, it has now become the avenue through which Kanye channels his narcissism.

Kanye West at a Sunday Service performance

When you look for the old Kanye, the place where the split happened is clear. Old Kanye ends with Yeezus, the album famous for the racial commentary on “Black Skinhead” and “Blood on the Leaves,” and the complex and emotional production of the Bon Iver collaboration, “Hold My Liquor.” Perhaps, old Kanye leaves us on the very last track of Yeezus, “Bound 2.” That song sounds more like anything on Pablo than on Yeezus, the song that was more spectacle than substance.

If we knew then what we know now — that he would one day wear a MAGA hat and say slavery was a choice — I would have just liked to be more prepared. Instead of looking for redeemable qualities in Pablo and hoping his ensuing albums would right the course (they didn’t), I would have let the old Kanye go so much sooner, and with so much less grief.

60

60