“I’ve never told anybody this, but that is about Kurt Cobain. It’s about him blowing his head off.” That was Chan Marshall talking to The Guardian in 2012. She might as well have said, “I’ve never told anybody this, but the sky is blue.” Everyone knew. Everyone knew the Cobain connection the first time that they heard “I Don’t Blame You,” the first song on Cat Power’s 2003 album You Are Free. I don’t remember ever entertaining the idea that “I Don’t Blame You” was not about Cobain. Certain things never really have to be said. Certain things are understood.

“Last time I saw you, you were onstage. Your hair was wild, your eyes were bright, and you were in a rage. You were swinging your guitar around ’cause they wanted to hear that sound, but you didn’t want to play. And I don’t blame you.” That was how Chan Marshall opened “I Don’t Blame You.” Right away, the meaning was obvious. So was the subtext.

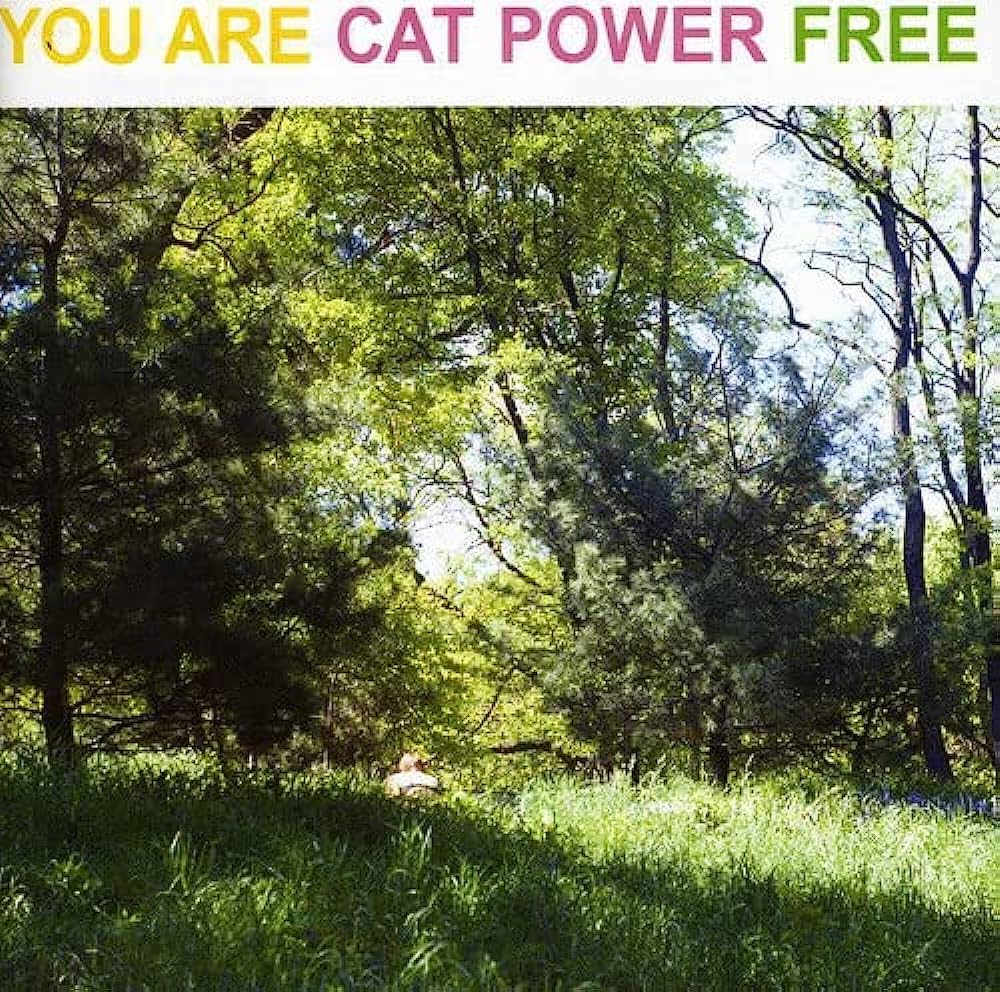

You Are Free was the first album of original Cat Power songs in five years. After Marshall had been moving in underground circles for years and after she’d considered leaving music behind entirely, 1998’s stark, skeletal, unsparing Moon Pix had turned her into a kind of cool-kid celebrity — someone who could model designer clothes in magazines. It also turned Chan Marshall into someone who would play her songs in packed clubs, with hundreds of people staring at her. This didn’t sit right with her.

Cat Power shows were notorious for their discomfort levels. There would be stories about Chan Marshall stopping shows in the middle, crying, running offstage. I never saw anything like that happen, but at the Cat Power shows that I saw in the late ’90s and early ’00s, I did see someone who did not like attention. The people who came to Cat Power shows weren’t lookie-loos, necessarily, but there was something performative about the way they’d yell encouragement at Marshall whenever she faltered in between songs. The vibe was fucked. Chan Marshall wasn’t famous-famous, but she was famous enough to flinch away from all those eyeballs.

Lots of Cat Power songs are about embracing oblivion, about the comforting appeal of the void. When Marshall finally consented to make another album, she had a big-money engineer and some extremely famous guest musicians, but she wasn’t trying to become a star. Instead, she reacted with horror whenever she saw herself becoming an abstraction in other people’s minds — something that you have to do to become a star or even a mid-level indie musician. “I Don’t Blame You” is a song of commiseration for someone who had to carry all the bullshit of millions of strangers, someone who was always seen but seldom understood. Maybe it’s also a song about Chan Marshall forgiving herself, rationalizing her own appetite for self-annihilation. But funny things happen when songs go out into the world. A few months after the release of You Are Free, an album that will turn 20 years old tomorrow, Chan Marshall found herself performing “I Don’t Blame You” on British television.

After Moon Pix made her semi-famous-ish, Chan Marshall retreated, which only drew people in more. When Marshall followed Moon Pix with The Covers Record, her 2000 collection of other people’s songs, it might’ve been a move away from the spotlight, but that album became its own kind of word-of-mouth hit. When Marshall finally recorded You Are Free, she seemed reluctant. Marshall produced the album herself, but she did it with a big-deal engineer. Adam Kasper had already produced huge records for the Foo Fighters, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Queens Of The Stone Age. He volunteered his services for whatever Marshall needed. Marshall wasn’t sure about him.

There’s a fascinating Pitchfork interview from the moment just before Cat Power released You Are Free. In the conversation, Marshall pushes back against many of the questions and even the idea that she should be doing the interview at all. She also describes how Adam Kasper came into her life. She says a friend recommended Kasper and that he volunteered is services as engineer, producer, whatever she needed: “I was like, hmmm… sounds a little too friendly, ’cause I didn’t know him at all… I don’t want anyone ever producing me unless I’m giving my soul to them. Like, unless they’re writing the songs and I love them so much and I want them to fucking tell me what to do. But I’ll never do that.”

Chan Marshall’s ideal collaborator, as she put it then, was “someone who will just shut the fuck up.” That was Adam Kasper. You Are Free is the first Cat Power album that couldn’t plausibly be described as “lo-fi,” but that doesn’t mean that it’s accessible. The album flits back and forth between Marshall’s misty, spectral ballads and fuzzed-out conjurings that sound, on at least level, like rock songs. A few of Adam Kasper’s other clients show up, but they keep their contributions minimal. Eddie Vedder sings backup on two songs, his baritone murmur adding ballast to Mashall’s hazy twang. Dave Grohl, Kurt Cobain’s old bandmate, plays drums on a few songs and bass one one, but he never drops bombs on the track. The most visible collaborator is Dirty Three/Bad Seeds violinist Warren Ellis, whose raw scrape was already familiar to Marshall.

Chan Marshall worked on You Are Free in between tours and travels, not following any particular plan. Sometimes, she worked with other musicians. Usually, she didn’t. Some songs seem engineered to win Cat Power a bigger audience. Some are about Marshall’s ambivalence about these theoretical bigger audiences. Some are both; “Free,” the album’s second song, is a spaced-out chug-rocker about the illusory nature of fame: “Don’t be in love with the autograph/ Just be in love when you love that song, on and on.” The recording process seems like it should’ve led to something slapdash and all-over-the-place, but Chan Marshall’s voice, authorial and otherwise, is too strong for that. Even the rockers carry the vaporous, languid strangeness that always set Cat Power apart.

Chan Marshall didn’t write every song on You Are Free. As ever, there are covers. Marshall turns Michael Hurley’s outsider-folk song “Werewolf” into a seance, and she reimagines blues great John Lee Hooker’s terse accusation “Crawlin’ Black Spider” as the lost, desolate incantation “Keep On Runnin’.” Those cover choices seem deeply deliberate. Chan Marshall might not phrase it in these terms, and she might not even think of these things consciously, but I see those two covers, at least in part, as Marshall’s way of setting herself apart from anything else that was happening in music in 2003. Marshall’s peers were not the other artists on the Matador Records roster or the ones populating America’s indie clubs; they were the ragged, ancient voices that found their way into your bones.

Some of the songs on You Are Free speak to a bottomless, overwhelming sadness. “Good Woman” is a howl of devotion from one broken person to another, while “Names” is a heart-wrecking catalog of the kids who Marshall knew when she was young. In Marshall’s telling, those kids went through Biblical travails: death, molestation, rape. One kid, Charles, professed his love to Marshall when they were both 14, but then Marshall moved somewhere else. Over a mercilessly quiet piano progression, Marshall sings what happened to Charles in the simplest terms imaginable: “He began to smoke crack. Then he had to sell ass. I don’t know where he is. I don’t know where they are.”

In that Pitchfork interview, Rodrigo Perez, the writer, asks Chan Marshall whether she really knew those kids. Her answer: “I know them. I don’t know where they are. My friend said he saw one, ‘Charles,’ and said he’s alive. But some of the other ones, I know I’ve tried to find on the…” She trails off for a second. She can’t think of the word “internet.” Then she whispers: “They’re not there.”

A song like “Names” should not be the kind of thing that you play in the background when you’re having dinner. But that’s the thing about Cat Power. In her writing, Chan Marshall digs deep into the depths of human desperation and depravity. But she always makes it sound so beautiful. Marshall’s voice — soft, honeyed, always somewhere flickering in the distance — still casts its spell even when she’s singing in an expensive studio. Her elliptical songwriting style never lost its core. You could only gloss up a Cat Power record so much.

Earlier this week, Lana Del Rey told Billie Eilish that she’d essentially learned to sing while listening to Cat Power: “Her low tones, I would practice them. The way she sang that song where she’s like, [sings] ‘Bay-be-doll,’ I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, I could sing like that.’ I realized I had a low register, too. And when I learned that she played a big concert in New York with her back turned to the audience, that was when I realized I might have a chance.” All of this tracks. Cat Power took all that darkness, and she made it pretty. She made it into the kind of thing that could glimmer softly in the background. That was her gift, and maybe it was her curse.

Freedom is a big theme on You Are Free. It goes way beyond the title. It’s at the core of a song like “I Don’t Blame You” — the freedom of annihilation, the freedom to let yourself become nothing. Listening to You Are Free today, I get the feeling that Chan Marshall believed general functionality to be a mere role, one that she could happily shrug off. About halfway into You Are Free, you will find “Maybe Not,” a trembling piano-ballad that almost reads as a fantasy: “We can all be free. Maybe not with words. Maybe not with a look. But with your mind.” Chan Marshall sang that song on the Late Show With David Letterman.

Chan Marshall did a lot of work to promote You Are Free. She did the kind of work that didn’t necessarily come easily to her. She gave interviews. She made a music video. She toured hard. I saw Cat Power for the second time on that You Are Free tour, and she was less halting, less visibly shaken, than when I’d first seen her a few years earlier. Still, I did not get the feeling that Chan Marshall wanted to be there in that room on that night. She seemed to be drawing into herself. I left that night thinking that the local openers, Lungfish side project the Pupils, had absolutely blown her off the stage. Dan Higgs was a weird and singular presence, too, but he was also a performer. Chan Marshall was not. Not yet, anyway.

Maybe that’s the basic appeal of Cat Power. You listen to those records, and you hear someone figuring things out. Chan Marshall operated as a raw nerve for years and years. She flinched away from people’s attention, and that made people want to pay more attention. Marshall struggled after she released You Are Free. She went through a bad breakup. Her drinking got worse. But Marshall survived. She eventually reached the stage of her life where she could be comfortable as a touring musician, and she’s been in that stage for a long time. She hasn’t released another album like You Are Free. Nobody has.

21

21