In The Number Ones, I’m reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart’s beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

Coldplay have always seemed more than a little embarrassed to be Coldplay. They were arena conquerors who wanted to be seen as aw-shucks everyday blokes, happy journeymen who always radiated envy for their art-rock forebears even as they sold millions more than most of those bands. Coldplay’s music was always relentlessly pleasant, and yet they still inspired wave upon wave of backlash, even as they continued to do massive business. They’re a bundle of contradictions, so maybe it’s appropriate that their big, serious art-rock reinvention finally conquered the Hot 100 on the strength of an Apple commercial.

When Coldplay first came to mass consciousness, they were part of a wave of British bands who seemed to want very, very badly to become the next Radiohead. Radiohead themselves had moved on from sweeping, dramatic, vulnerable sincerity, opting instead for glitchy abstraction. In the process, Radiohead left a vacuum. Somebody else, surely, was going to come along and conquer festivals with majestically bummed-out introvert anthems, and many hopefuls were waiting in the wings: Travis, Keane, Snow Patrol, Muse, Elbow, Doves, Starsailor. Those bands all went on vastly different career journeys, but at the beginning, they all seemed to want the same thing. (Radiohead’s highest-charting Hot 100 hit, incidentally, is still “Creep,” which peaked at #34 in 1993.) Coldplay were right in the mix — or, at least, that was the perception.

This wasn’t especially fair to Coldplay, who had Radiohead’s knack for soothing falsetto wails but who seemed way more interested in chasing the ghost of Jeff Buckley. Initially, Coldplay stood out from their competitors because they had one crucial element: a singer who seemed willing to play the pop star, to take on the shy-dreamboat role that Thom Yorke had so forcefully rejected. Eventually, Chris Martin became something else, a playfully bashful ham who turned out to be way more Bono than Thom Yorke.

Chris Martin comes from the English city of Exeter. (Eagles’ “New Kid In Town” was the #1 song in America when Chris Martin was the new kid in town. In the UK, Leo Sayer’s “When I Need You” was sitting at #1 that day.) Martin’s father ran a caravan dealership, and there are a few Tory politicians in the extended Martin family tree. Martin went to boarding school and then majored in Ancient World Studies at University College London, which sounds like a fake name for a school but which is, in fact, the second-biggest college in the UK.

In his first week at UCL, Chris Martin met guitarist Jonny Buckland, and the two of them hatched plans to form a band. Bassist Guy Berryman and drummer Will Champion joined up later. The group recorded a few demos under the name Big Fat Noises, and if they’d kept that name, they would’ve never ended up in this column. They played their first shows as Starfish, which is better, and then they settled on the Coldplay name, which has served them well. In 1998, Chris Martin’s childhood school friend and original Coldplay manager Phil Harvey financed the recording of the band’s self-released debut EP Safety, which essentially served as a demo tape.

After playing a bunch of shows around the UK and guesting on DJ Steve Lamacq’s BBC radio show, Coldplay got the British indie Fierce Panda to release their 1999 EP Brothers & Sisters. That record made it to #92 on the British singles chart, and it led to Coldplay signing a major deal with Parlophone. They released their debut album Parachutes in 2000, and they made it to #35 on the UK charts with first single “Shiver.” But Coldplay really became stars on the strength of their next single, the swooning power ballad “Yellow.”

“Yellow” is such a banger. Guitars shoot up and explode like fireworks while Chris Martin begs you to look at the stars, look how they shine for you. It’s beautiful sensitive nonsense, and it was helped enormously by its video. The whole band was supposed to be in that clip, but Will Champion’s mother’s funeral was that day, so he couldn’t be at the shoot. Someone decided that Chris Martin should star in the video by himself, and the whole clip is just him, in slow motion, walking along a seashore at sunset. It turned Martin into a heartthrob and all the other Coldplay guys into permanent afterthoughts, though the band’s lineup hasn’t changed since.

In the UK, “Yellow” was a #4 hit. Parachutes debuted at #1 and went platinum nine times over. “Yellow” also made an impact in the US, a notoriously difficult place for young British rock bands to make any commercial noise. Here, “Yellow” peaked at #48, and Parachutes sold steadily, eventually going double platinum. Coldplay didn’t wait too long to follow that album. Their sophomore LP A Rush Of Blood To The Head came out in summer 2002. For that record, the band smartly steered away from the Radiohead comparisons, moving instead toward a vast and glossy version of Unforgettable Fire-style messianic arena rock, gesturing at the dramatic sweep of dance music without embracing electronic thumps.

The first time I saw Coldplay was at an alt-rock radio station’s Christmas show in a DC arena. Most of the other bands on that bill were closer to what might be considered cool: Queens Of The Stone Age, the Vines, Billy Corgan’s short-lived post-Pumpkins band Zwan, a random-ass James Brown performance. Coldplay seemed a little self-conscious about being the softest band on the bill, but they were also the only band who really seemed to belong in an arena in 2002. Their music was wimpy and comforting, but it was wimpy and comforting in the best ways, and it resonated. The band’s single “Clocks” reached #29 in the US and won Record Of The Year at the Grammys, beating “Hey Ya!” and “Crazy In Love” and “Lose Yourself.” It’s still my favorite Coldplay song.

A Rush Of Blood To The Head went quadruple platinum in the US; it’s Coldplay’s highest-selling album over here. Chris Martin married Gwyneth Paltrow in 2003, and their daughter Apple was born the next year. While becoming gigantically famous and popular, Coldplay earned a kind of grudging critical respect. They lost that with their next LP, 2005’s blander and sleepier X&Y. I think X&Y has some tracks, and I’m not going to get snobby about the beautifully wussed-out “Fix You,” a song that peaked at #59 over here and then turned up on a million movie soundtracks. But X&Y felt like a band on cruise control. Given that Coldplay were already easy targets, that perception plunged them into the realm of the perilously uncool.

No massively popular rock band is ever going to escape backlash, and Coldplay were still ultra successful. X&Y went triple platinum, and lead single “Speed Of Sound” gave the band their first top-10 hit in America when it debuted at #8 before plunging down the charts. (“Speed Of Sound” is a 7; its biggest problem is that it sounds a lot like “Clocks” without actually being “Clocks.”) With all that success, Coldplay were quickly becoming avatars of basicness, and they knew it. In the ultimate self-aware move, Chris Martin lampooned his own image on an episode of Ricky Gervais’ HBO show Extras, doing a very good job playing himself as a self-important asshole.

Coldplay took on another very funny role in the mid-’00s: They became every A-list rapper’s favorite rock band. I have no idea what was going on there. This strange phenomenon effectively launched the cliché that rappers have terrible tastes in rock bands. (I don’t think this cliché holds water. Coldplay were pretty good back then!) Chris Martin even collaborated with a couple of those rappers. In 2006, Martin sang the hook on “Beach Chair,” one of the worst songs from Jay-Z’s out-of-retirement album Kingdom Come. A year later, Martin popped up on the Kanye West single “Homecoming,” which peaked at #69.

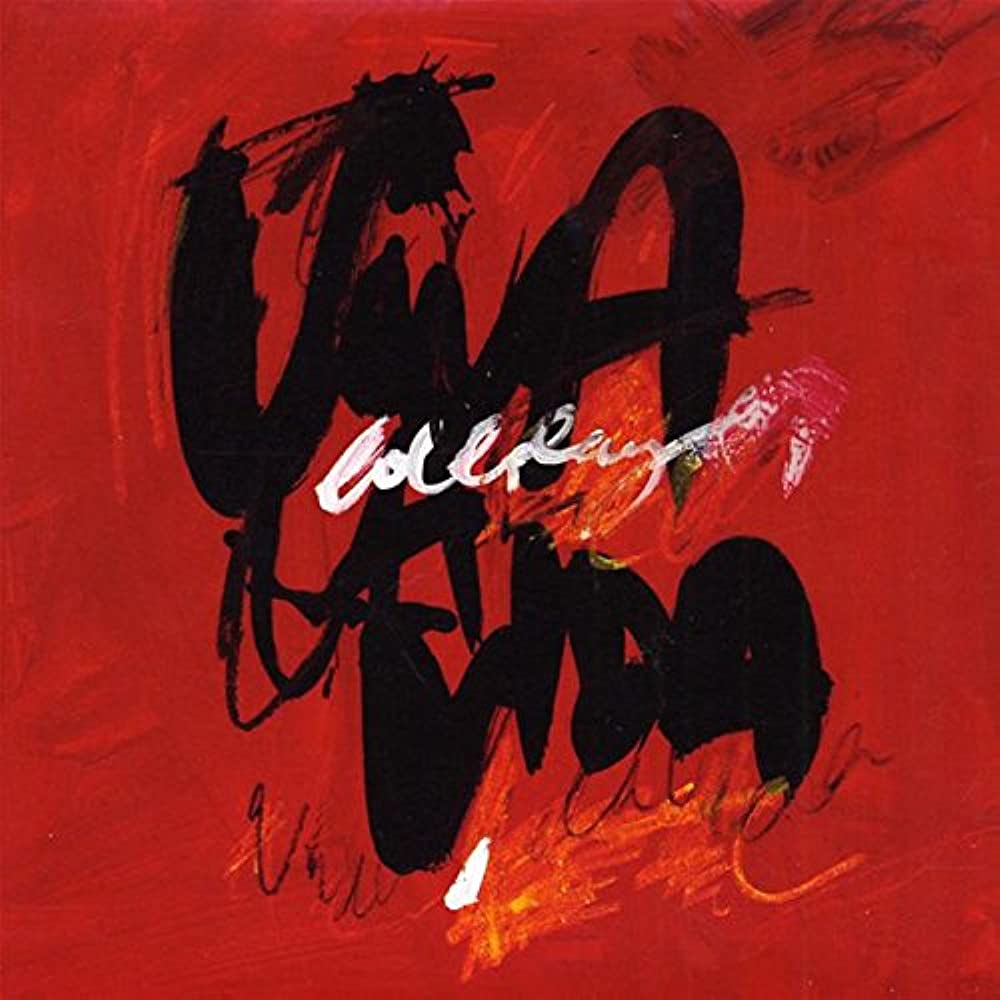

When they recorded their X&Y follow-up, Coldplay presumably wanted to fight against the perception that they were whiny soft-rock babies, and they were smart enough to realize that they couldn’t overtly capitalize on the fact that rappers liked them. Instead, they went in a more time-honored direction. For 2008’s Viva La Vida Or Death And All His Friends, Coldplay ditched Ken Nelson, the guy who produced their first three albums, and called up Brian Eno, the man who’s historically been the top choice for huge rock bands attempting to reinvent themselves.

Brian Eno lived a lot of lives before he worked with Coldplay: Roxy Music member, art-rock groundbreaker, ambient music inventor, co-conspirator with Davids Bowie and Byrne. Eno has been in this column a couple of times for co-producing U2’s iconic ’80s hits, and I have to imagine that’s the main reason that Coldplay wanted to work with him. Eno had some co-producers: British sound engineer Rik Simpson, Arcade Fire collaborator Markus Dravs, architectural dance auteur Jon Hopkins. Together with those producers, Coldplay came up with a vast, pretty, orchestral take on their own style.

Viva La Vida is full of church bells and kettle drums and majestic sonic smears of unknown provenance. The record has all the hallmarks of a difficult, experimental album from a popular band. At the end of the day, though, it’s still a Coldplay record. Even at their most dense and ambitious, Coldplay can’t help but make agreeably pretty music that sounds good echoing around an arena. Lead single “Violet Hill” was a pretty good indication of where Coldplay were going with Viva La Vida. The song was a little grander and more self-serious than previous Coldplay joints without being too much of a stylistic left turn. Still, “Violet Hill” wasn’t really a hit; it peaked at #40.

Maybe the problem was that “Violet Hill” wasn’t in iPod commercials. The iPod commercials — black silhouettes dancing with white earbuds in their ears — were all over the damn place in the ’00s, and they turned a lot of songs into hits. U2’s “Vertigo” didn’t exactly get a huge boost from its iPod ad; the song only made it to #31 upon its 2004 release. But a different iPod ad definitely helped the previously unknown Australian rockers Jet’s song “Are You Gonna Be My Girl” reach #29 that same year. A year later, the Gorillaz/De La Soul collab “Feel Good Inc.” sailed to #14 on the strength of an iPod ad. And in 2007, the colorfully twee video for the Canadian indie-popper Feist’s “1234” showed up in an iPod Nano commercial and pushed that song all the way up to #8. (It’s a 7.)

When Chris Martin and Gwyneth Paltrow named their daughter Apple, it seemed like standard weird-rich-people behavior. When Martin himself showed up in an iTunes ad a few years later, that decision came to look like deeply cynical corporate synergy at work. Coldplay’s iTunes ad wasn’t just built around random silhouettes dancing to Coldplay. Instead, Coldplay themselves became the silhouettes — with just enough light on them, and just enough swirly colorful smoke surrounding them, that you could still tell they were Coldplay. The ad even mentioned that Coldplay’s new song was called “Viva La Vida” — helpful, since those words never actually appear in the song.

Coldplay named “Viva La Vida” after a Frida Kahlo painting, which went along with their decision to use a Eugène Delacroix painting as their album cover. On “Viva La Vida,” Chris Martin sings from the perspective of a deposed tyrant who’s lived long enough to see himself become a villain and who knows he’s not getting into heaven. He used to rule the world. Seas would rise when he gave the word. Now, he sleeps alone and sweeps the streets that he used to own. Revolutionaries wait for his head on a silver plate. He’s just a puppet on a lonely string. Aw, who would ever wanna be king?

Chris Martin has never come out and said exactly what the fuck he’s talking about on “Viva La Vida.” There’s plenty of Biblical imagery on the song — pillars of salt and pillars of sand, Jerusalem bells a-ringin’. But people have speculated that the song depicts the final moments of Louis XVI, the dethroned monarch who to proclaim his own innocence before meeting the guillotine. You could read “Viva La Vida” as the metaphorical desperation of a rock star facing down his own obsolescence — not unlike Eagles on “New Kid In Town,” come to think of it. But I have a half-baked theory that “Viva La Vida” is really a love song. There’s one line on there in the second person: “Once you’d gone, there was never, never an honest word/ And that was when I ruled the world.” I hear that as Martin imagining his own post-breakup desolation in the most majestic terms imaginable.

Whatever the case, “Viva La Vida” is certainly not built from the same lyrical stuff as most of the songs that have topped the Hot 100 this century. The song also stands on its own musically. The strings are the first thing you hear — the jaunty little riff that arrives just before Chris Martin remembers when he used to rule the world. The strings get busier and busier, and they overwhelm any traditional rock-band instrumentation in the mix. Eventually, we get drums and bells and sitars and all sorts of elements that I can’t even name. The chorus, the bit about Roman cavalry choirs singin’, only arrives at the end of the song, right before the massed “whoa-ohh-aaaoooh” arena-singalong vocals that serve as the song’s real hook.

“Viva La Vida” is certainly impressive as sheer sonic spectacle, and it’s fun to hear Chris Martin get all grandiloquent about the end of his royal reign or whatever. The song also has a real central melody that shines through all the production, and it’s got momentum and energy on its side. The lyrics might be maudlin and self-serious, but the music never quite gets there. In the context of 2008 pop music, the song stood out. But Coldplay definitely wanted to make a masterpiece with “Viva La Vida,” and I don’t think they succeeded. Instead, they managed a pretty nice song that was full of bells and whistles. I’ll happily accept that, but “Viva La Vida” was never going to make Coldplay into beloved rock messiahs on the level of U2, or even on the level of Radiohead.

It took a whole lot of marketing muscle to turn “Viva La Vida” into a #1 hit, even for a week. The song got two videos — one from the master Hype Williams, who really just filmed the band in front of that Delacroix painting, and another from Anton Corbijn, who’d already made the Ian Curtis biopic Control. In Corbijn’s video, Chris Martin wore a crown and stared forlornly out to sea — an obvious nod to Corbijn’s classic 1990 clip for Depeche Mode’s “Enjoy The Silence.” (“Enjoy The Silence” peaked at #8. It’s a 9.) Those two videos, the iTunes ad, and the usual blitz of talk-show performances were enough to make “Viva La Vida” into a #1 hit for a single week. It was not an easy thing for a rock band to top the Hot 100 in 2008, but Coldplay pulled it off.

After all that, the Viva La Vida album didn’t sell as much as X&Y or A Rush Of Blood To The Head. The album went double platinum and no more. Coldplay released “Lost” as their follow-up single, and they got Jay-Z to rap on a remix of the song, but it only climbed as high as #40.

“Viva La Vida” also forced Coldplay to deal with one of the headaches of being a successful act in the ’00s: A whole lot of people thought that the band had stolen the song. Veteran guitar shredder Joe Satriani sued Coldplay, claiming that the band had plagiarized his 2004 instrumental “If I Could Fly.” (The two songs do share a melody, but I have a hard time imagining the members of Coldplay sitting around and listening to latter-day Satriani albums.) Coldplay settled that lawsuit out of court, and they also dealt with accusations from an indie band called the Creaky Boards and from Yusuf Islam, the man formerly known as Cat Stevens.

Even with those accusations, “Viva La Vida” solidified Coldplay as a globally gigantic band, and they continue to tour stadiums around the world to this day. Chris Martin has also remained tremendously famous; when he and Gwyneth Paltrow broke up in 2014, they introduced the term “conscious uncoupling” into the lexicon. Martin is now living with Dakota Johnson, so he’s doing just fine for himself. Still, I get the sense that Martin loved having the #1 song in America, that he’s been trying to recapture that feeling ever since.

Coldplay have definitely been chasing hits ever since “Viva La Vida,” and they haven’t always been successful. The band recorded singles with Beyoncé and Rihanna, and neither of them made the top 10. (“Princess Of China,” with Rihanna, peaked at #20 in 2012, and “Hymn For The Weekend,” with Beyoncé, stalled out at #25 two years later.) “Every Teardrop Is A Waterfall” and “Magic,” the lead singles from Coldplay’s next two albums, both peaked at #14. Coldplay didn’t return to the top 10 until 2014, when “A Sky Full Of Stars,” their collaboration with the late Swedish dance producer Avicii, peaked at #10. (It’s a 6.)

But Coldplay kept trying, and they finally landed another major hit in 2017. “Something Just Like This” is billed as a song from Coldplay and the Chainsmokers, the bro’d-out EDM duo who will eventually appear in this column. Really, it’s just Chris Martin singing on a Chainsmokers track — a sign that Coldplay have entered the Maroon 5 zone where any song with Chris Martin vocals automatically counts as a Coldplay song. In any case, “Something Just Like This” came out during a strange period of Chainsmokermania, and it peaked at #3. (It’s a 4.)

In 2021, though, something really fucking crazy happened. Coldplay joined forces with two different dominant pop entities, and they somehow managed to eke out another #1 hit. The forces at work behind that song make the “Viva La Vida” Apple commercial look like a model of artistic integrity, but the band pulled it off. We’ll see them in this column again.

GRADE: 7/10

38

38