Even if you don’t know who Ebru Yildiz is yet, you’ve at least seen her photos: She’s photographed notable artist portraits for the likes of Lucy Dacus, Interpol, Pink, Idles, David Byrne, Uproxx cover star Snail Mail, and perhaps most famously, Mitski.

Born and raised in Ankara, Turkey, Yildiz moved to New York City in 1998, but she didn’t start taking photographs right away. It’s her intercontinental journey from music lover to noted music photographer that brings Yildiz into the Sound + Vision limelight (her work with Mitski yielded a nomination for Best Merch Design).

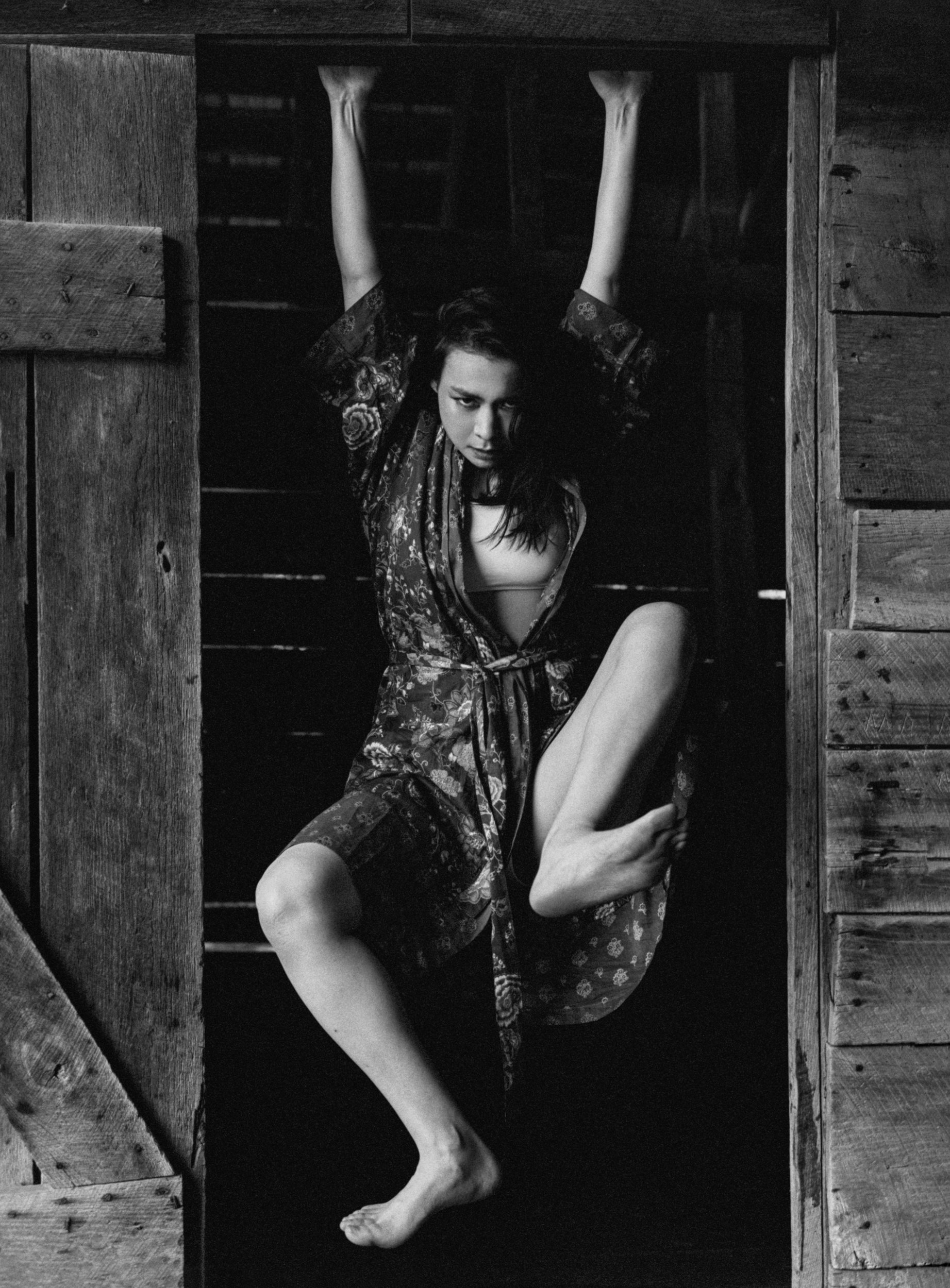

Yildiz’s passion for her craft is palpable in her images. This isn’t just someone who loves to take photos: This is a photographer who loves to get to the root of her subjects and the stories beneath their skin. While she shoots in both color and black and white mediums, it’s in the latter that Yildiz’s style leaves the most lasting emotional response. There’s a raw humanity captured in her shots where an artist seems to show multiple sides of themselves with just one look. Her work with Mitski on the singer’s latest album, The Land Is Inhospitable And So Are We, doesn’t just grace the cover of the album. A series of shoots help to peel back the layers of the artist’s mystique, uncovering the stories within the gorgeous, fractured Americana of the album and prod at the essence of what makes Yildiz’s subject a generational one.

Yildiz shoots for magazines, labels, and her own personal projects, like Phosphene, a photography zine featuring some of her favorite subjects. The love of the game is at the core of Yildiz’s work and it’s what makes her a unique and important figure in music photography today. We caught up with her by phone from her home in New York City, shortly before she took off to Turkey, where she was curating a photography exhibit entitled Beyond The Spotlight: Chronicles In Music History.

“So many of my heroes and friends are in it,” said Yildiz, a perfect envoy to make sense of the visual side of the music world.

What brought you out to New York in 1998 initially? Were you already into photography?

No, I actually came to study advertising and marketing [laughs]. So it wasn’t related, but I grew interested in the graphic design part, and within that, I got interested in photography. I randomly took a printing class that got this all started. My love for music has always been there, so I started taking my camera to concerts. Before that, I don’t think I was very good at shooting anything. I would try to take photos on the street and stuff, and I don’t think my personality suits that. I sucked so bad! So when I started taking photos at concerts, I was excited because I really loved it.

At what point did you move away from concerts and get into shooting portraits for musicians and artists? Was there some proverbial “big break” moment, or somebody you worked with that just led to more?

I’d always been interested in portraits, but I wouldn’t dare to do it at first. When you’re shooting a concert, you don’t have to interact with anyone, and you can do whatever you want in a photo pit because you’re not dependent on the other person: You’re working on your own and you have no direct connection with the person you’re photographing. So that felt comfortable, yet it was my natural gateway into taking portraits, because I started taking photos of my musician friends.

When you start taking portraits, your personality starts coming into play. You have to be talking with people, and at the same time, you have to be directing what you want to do and be in control of the light. It’s more challenging in many ways and this is why I was scared of portraits in the beginning. But there was also a fear of that human interaction, because I started as a fan. Whenever I’m shooting, I’m their biggest fan, that admiration is in play, but you don’t want to come across like it. There’s a real critical balance, too. It took time and eventually I made a conscious decision to not shoot live music anymore and to shoot only portraits. I threw myself into that and rented a small studio and focused on portraits from then on.

You’ve worked with people who are enigmatic, like Mitski, or even Julian Casablancas recently, who’s notoriously very particular about the way he looks in photos. How do you break down that wall you’ve alluded to, to make them feel comfortable and to be able to create alongside them?

First of all, I need to prepare myself before the shoot starts in a lot of ways, even if it’s an artist that I’m already familiar with. I do a lot of research to see what’s out there, how they photograph, and what works for them, just to get an idea of general visual history that they have on the internet, along with their personal history, so I know things about them that I can talk to them about. I go into the shoot knowing what I’m gonna do, but once a shoot starts, plans dissipate often, because it totally depends on the interaction you have with the person or what kind of mood they’re in. It’s the preparation that puts me at ease, because I get insanely nervous before every single shoot [laughs], regardless of who I’m shooting. I have butterflies all the time. Until the minute I meet them, I’m so nervous. But once I meet them, everything just kind of slows down in my head because I know I’m prepared and I get into work mode.

Once I’m there, during the shoots — full day, half day, whatever — I don’t eat, drink, or go to the bathroom. I’m completely in it. Taking photos really excites me. I love, love, love it, and I think people realize that I love what I’m doing, so it becomes contagious and they want to be a part of that. I talk a lot and ramble sometimes because I have to stop midway to tell them to turn left or look up… madness during the shoot.

It’s interesting the way you describe that, of how you try to get a reaction or have your subject share that passion and sink into the process, because I see a lot of that in the latest The Land Is Inhospitable And So Are We shoot with Mitski. I think I can say pretty definitively that it’s some of your best work. It’s so visceral and raw, and you get so much out of her in these photos — different reactions and sides of her that come through in these images and inspires so much in my mind. Take me into that photo shoot in Nashville. What was it like?

I met Mitski way back in 2016 when she was doing photos for Puberty 2. Not the cover, but her press photos. So we already had a relationship that started eight years ago or so, and we’d done other shoots recently, like the album artwork and press photos and a [Phosphene] zine together. So we had a relationship, a little bit of history, and that brings some trust, so we both know what we’re capable of in a way.

That shoot is a really, really special one. Let me start from the beginning: When I started that project, she sent me some inspirations and said that she had a couple of things in mind. I took that and turned it into a 10-page inspiration board, and we had an idea of what we wanted to do in general. We rented a location and spent three days there, part days so we weren’t exhausted.

I have to say, a lot of things depend on how invested the person you’re photographing is, and Mitski has always been really invested. She’s one of those artists who never does anything half-assed. If she’s doing a photo shoot, she’s doing it and gives her energy, does her best so you can do your best.

The shoot was really intimate. She didn’t want any styling, any hair or makeup. To be honest, all the females in the music industry are expected to look a certain way. Usually, the inspiration is something more glamorous, but our inspiration board was this imagery that was a little bit grotesque — she didn’t really fit into what people expect from her. There was a specific way that she wanted her audience to experience her art and her album.

As a photographer, especially a female photographer, we all grew up with the male gaze. All the white male photographers told us what a woman needs to look like. So when I started photographing, I made a point that I don’t want the woman that I photograph to look that way. I want a woman’s strength to show through their personality and not necessarily how they look or all the other stuff.

That totally comes through for sure.

I’m not saying that I don’t want to make the women that I photograph beautiful or powerful. But I don’t think the beauty or sexiness or this and that that people seem to be concerned with has to come through physical appearances, if that makes sense. I feel like every woman that I photograph is incredibly beautiful in their own specific way. So this shoot with Mitski was the ultimate representation of that. She didn’t even ask to see the photos even once midway through, or say, “Is my hair looking good,” or whatever. There wasn’t anything like that, which was very freeing on both of our ends. It was one of the most wonderful shoots I have ever done. I remember as we were leaving, I thought, “This is one of the best things I’ve ever done and I haven’t even seen the photos yet.” It was the feeling and it felt so good and really right. It was excellent.

So like in this shoot, you work a lot in black and white. What is it about that particular medium and aesthetic that’s powerful for you as a photographer? What is it that you get across in black and white that feels different for you in what you’re trying to evoke as opposed to full-color images?

I love color photos, too. There’s time and place for it, and if the project I’m working on requires it, I have no problem working in color. But I prefer black and white for my personal work. The reason behind it is multifold: One of them is that color is very time-specific in my head. Like when you see a color photo from the ’60s and ’70s, you can tell the time period immediately. Same goes for the 2000s when digital came along. And the other thing is, when you look at a color photo, I feel like the first thing you see most of the time, you get distracted — I go for emotion and mental state in my photos and I think that a lot (most) of the time, color kind of complicates that, because your attention gets distracted with colors. When it’s black and white, it removes one level of distraction so you’re more focused on the photo.

Most importantly, all my inspiration, all the photographers I look up to — Diana Arbus, Sarah Moon, Deborah Turbeville, Bill Brandt, Jim Marshall, Irving Penn, Richard Avedon — are from older times, where color photos weren’t even in the picture. That has an effect. I also first started photography in a black and white printing dark room. So there are all these different levels to it. Some are practical, some are conscious, and some are unconscious decisions.

One thing I really like about your work is that it’s not just limited to Pink or Interpol or Mitski. Looking at some of the acts you’ve worked with a lot, like Chelsea Wolfe — I love your Chelsea Wolfe photos — Emma Ruth Rundle, A Place To Bury Strangers, other more emerging acts, I get a sense that you work with a lot of artists that you love, or as you mentioned earlier, friends. How do you balance that, working on the things you love and matter the most to you while also trying to make a living at the same time?

To be honest, I love doing personal projects. In the past, some of my inspirations were Life photo essays. In the past, publications used to assign photographers and send them out to places for days at a time to get a photo essay about a person. I find that really meaningful, because you get to see different aspects of a person. I really wanted to do that because there wasn’t anyone out there willing to assign me anything like that. So I started doing personal projects. What better way to do that than reaching out to people that you actually love?

While I do work with bigger artists, it’s not as if I wouldn’t work with anyone who doesn’t have X number of followers. Most of the time, I don’t say no to jobs. I accept what comes to me. Because of that, I got introduced to a lot of emerging acts, like photographing Mitski for the first time eight years ago. Sure, she was known then, but not like she is now.

Yeah, you shot Idles six years ago and look at where they are now.

Yes! With Idles, I heard one song on a friend’s Instagram Story when they were playing a show in New York. I didn’t even hear a full song, just part of one on his Story, and I fell in love with them. I didn’t even see the band, just heard the music.

So their label [Partisan] is one that I work with a lot and photograph a lot of their artists. I reached out and I said, “Who is this band? I’d love to take some photos with them if they have time.” And it kinda happened the same day. They played one night, and the next day, I was taking photos and I hadn’t even seen them live at that point. It’s a perfect example because I really enjoyed their music and wanted to have a record of them as a photographic document in a way.

What kind of advice would you give to creatives or aspiring photographers who are trying to find their way or channel their passion, or maybe they already are and want to take it to the next level?

The most important thing is for them to keep going. Sometimes the expectation, especially with Instagram and such, people are oftentimes after overnight success. In my experience, it doesn’t happen that way most of the time. If you’re going in for immediate success, you might be setting yourself up for failure. Instead, if you’re doing it because you love doing it, you just need to keep at it until you can make money from it. Until that comes, there’s no shame in making money from other jobs.

Like anything else, I have no doubt that if anyone has passion for it and keeps doing it, regardless of recognition or getting money or not, if they keep doing it, I can’t see why they wouldn’t be successful.

70

70