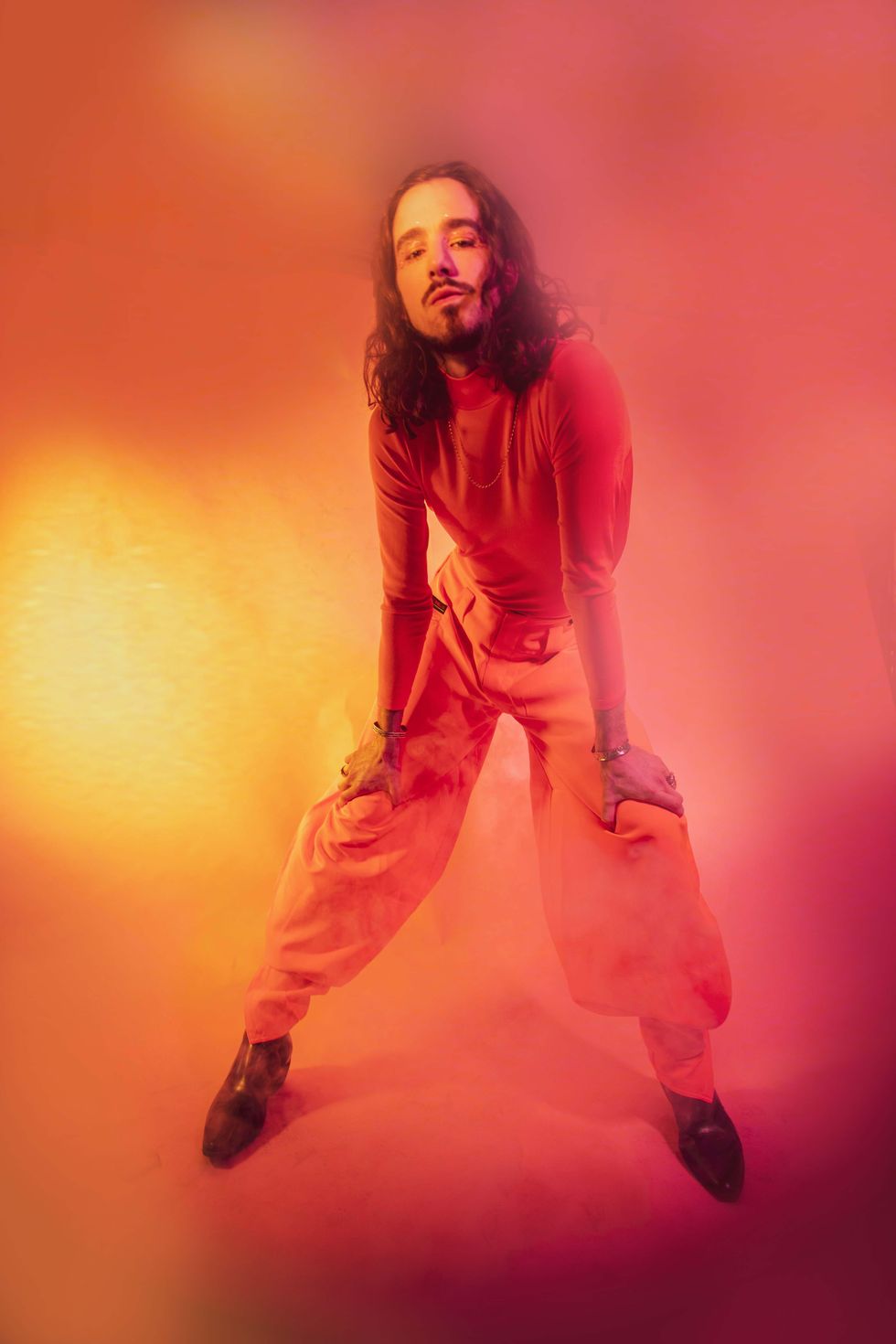

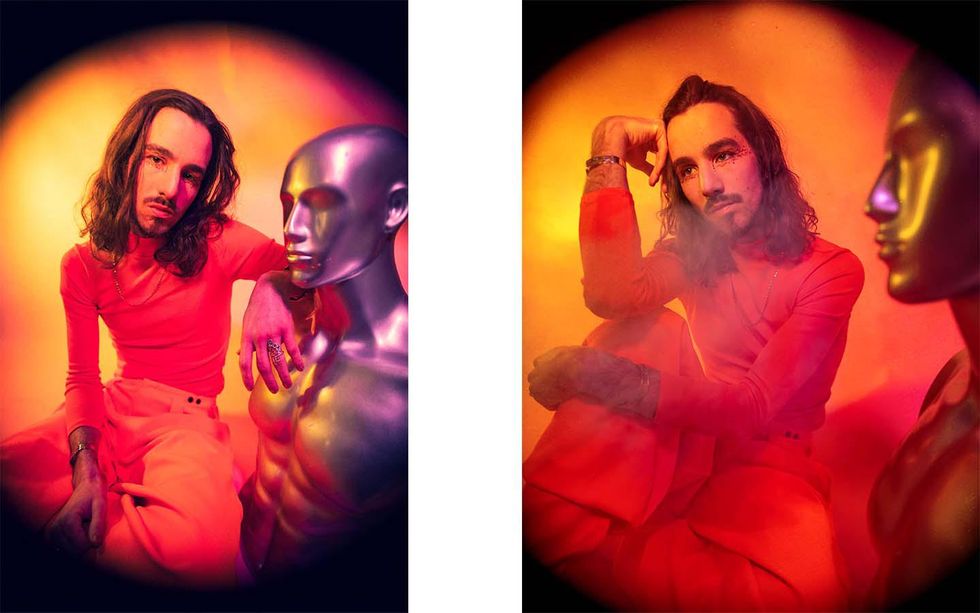

Photos by Meghan Marshall

Interview by Jordan Edwards

For years, Miles Francis has been one of the music industry's most dependable instrumentalists. The New Yorker has shared the stage and/or studio with acts including Will Butler of Arcade Fire, TEEN, Antibalas, Allen Toussaint, and the late, great Sharon Jones.

Now, Francis has stepped out with a new solo album, Good Man. Many of the album's 12 tracks explores masculinity and the social construct of the male ego. Although they've been interested in the subject for years, the idea became amplified after coming out as nonbinary in 2021.

I’ve known you as an instrumentalist for different bands for a long time. What pushed you into concentrating on making solo music?

I’ve been making my own solo music since I was a child, when my dad would help me record my own songs on his tape machine. The focus was always on the drums, though, since they were my first instrument and my identity. So, as I grew up, I started to get gigs playing drums for bands, and when I joined Antibalas at 19 years old, my professional career as a drummer took off on its own. The whole time, though, I wrote songs too. It wasn’t until I met Will Butler of Arcade Fire that I realized I should pursue my own voice. I was opening for Arcade Fire with Antibalas, and I watched them perform every night. I’ll never forget watching Will perform – I was drawn to him, and would ask him all sorts of questions after each show. Then, when I joined his solo project as his drummer, I saw him work up close, and it gave me a lot of confidence as a performer in my own right. The way Will moved, the way he captivated crowds–it had a massive impact on me. Fast forward years later, and I’ve finally released my own album as a solo artist. I am grateful for every step along the way.

You come from a musical family. I’m assuming you started playing at a young age. What was your first instrument, and what is your best instrument?

I was drawn to the drums first, and I got a drum set for my sixth birthday. The drums are my home base, the prism through which I see everything else. To me, everything is rhythmic, and that’s because I’m a drummer at heart. But when I was a kid I got great satisfaction out of approaching other instruments like a drummer–playing guitar like a drummer, playing keyboards like a drummer, even singing like a drummer. Eventually, I played all those instruments so much that my main “instrument” morphed into songwriting and producing. Drums were the beginning, but writing and producing a song is my grander purpose in life.

Did you play everything on Good Man?

It’s a lot of me, since I love bouncing around my studio layering different instruments myself. I’ve been doing that since I was a child, and that process gives me so much joy. For this album, though, I wanted to expand my sound past my own usual field of vision, so I invited in some guests. Lizzie Loveless and Lou Tides (formerly of TEEN) sang background vocals, Lollise Mbi and Giancarlo Luiggi played shekere, and Maria Christina Eisen played baritone saxophone. I wrote string arrangements that were played by Camellia Hartman and Meitar Forkosh on violins and Midori Witkoski on viola. Last but not least, my father Leif Arntzen played trumpet, which is special to me, because my dad has been a beacon of creativity and music for me since I was a child.

One theme you explore is masculinity and the male ego. Is this a result of you coming out as nonbinary, or is it a subject you’ve always been interested in?

Throughout my music videos, I use a giant silver mannequin (who I affectionately call Silverman) to represent an archetype of masculinity – a menacing yet obsolete vision of the ideal Man. I’ve been in an internal conversation with manhood my entire life, yet I’ve only been able to put it into words in the last few years. I started looking closer at the male ego around the #MeToo resurgence in late 2017. I was starting to see fractures in thought amongst the progressive-minded male friends in my orbit, through conversations we were having about various #MeToo scenarios. We all agreed on cases like Trump and Harvey Weinstein, but the Louis C.K.'s and Aziz Ansari's of the world started to produce anxious and defensive reactions among men, which I found surprising and disappointing at the time. When you hear news of a woman breaking her silence about a man’s inappropriate behavior, and your first reaction is to bemoan cancel culture or say “Oh, I can’t even put my arm around a woman anymore," it’s a giant red flag and a signal of deeper issues. Men seemed to have this gut reaction to the idea of accountability for their behavior, and that was when I began thinking of the lyrics that eventually became the Good Man album. I began reflecting on my own behavioral tendencies and what I was seeing around me, and each song on the album became a little case study that altogether zoomed out to make a portrait of a man in crisis. By the end of the process of making Good Man, and through over a year of drumming for weekly Black Trans Lives Matter protests (biggest heartfelt shoutout to Qween Jean!), my perspective on my own manhood had evolved, and I found nonbinaryness.

The album’s production has a ton of layers. It sort of reminds me of The Beatles meets Talking Heads. What was it like to gather and record all those sounds?

Two of my favorites – thank you! Production is my way of communicating with the world, so there are naturally layers. Ebbs and flows, addition and subtraction, crests and troughs like ocean waves – that is what I love about production. I am a solo artist, but I approach my productions like a band. Then, when I’m done tracking, I put on my editor’s hat and decide what should shine and what should recede. One of my biggest influences is Fela Kuti, and I’ve written and played a lot of Afrobeat music. His songs were recorded by a 10 piece or larger band, yet each instrument served a specific compositional role that added up to one giant breathing organism. That is how I approach my music – I try not to add a part unless it is serving a purpose and serving the song. Sometimes that means it’s a dense song, sometimes it turns out to be a minimal song. As long as the sound is serving the song, then it stays.

Was it a pain to mix and master?

Andrew Lappin mixed the album and handed it to Joe LaPorta to master. I don’t mix my own music, because I’m way too close to it, and it’s healthy to hand it off at that point in the process. Andrew (who also worked on L’Rain’s great recent album Fatigue) did a great job at focusing my songs’ sound. My songs can be dense at times, but he knew what to bring forward in the mixes, and we ended up muting some elements in the mixing process because it was just clouding the mix. Plus, he is phenomenal at mixing drums, so as a drummer I was very satisfied.

You make these great videos where you film yourself playing multiple instruments and layer the clips together. Is making those as hard as it looks?

They definitely require a lot of focus! First, I have to decide the camera angle and where each Miles clone will be located. Once I start filming, I can’t move the camera, otherwise the cloning effect gets messed up. I have to make sure to plan the musical element in advance, too, because it’s all in my head as I’m recording piece by piece. For example, if I record the drums first, I’m just recording solo drums, so I have to hear the rest of the song in my head to get it right. On top of that, I have to make sure to keep it loose, so the end product is natural and flowing, not robotic. The process is actually analogous to my normal recording process, because when I record a song, I am playing music with myself, adhering to the same values. The only difference is the film element.

Your parents, especially your dad, appear in a lot of your imagery. Are they really into it, or just being supportive?

Once I had the idea to include my parents in my album’s imagery, it unlocked a whole trove of ideas and helped me clarify what this album is all about. The question of someone’s nature – “why am I like this? where did these impulses come from?” These are questions I’ve asked myself many times over the years. Besides the impact of society and culture on a person, it goes back to family. I’m an only child, so it’s always been just my parents and I, and they have each influenced me in their own way. I wanted to play that up with them in the visuals, and they’ve been completely game for whatever weird concepts Charles and I dream up. There have been conversations along the way, though, where one of them will ask, “So Miles, what exactly does this video mean?” My dad is a musician and my mom is a music lover, so they understand my obsession with making music and art, and for that reason the album is dedicated to them.

Now that the album has been out awhile, how do you feel about it?

Underneath it all, I feel relieved. I’ve been carrying this album for years. It feels good that it is all out there. It’s a little vulnerable, because I’ve relinquished the power to the public, but releasing music is what I am on this Earth to do. I have a deep-seated feeling of being understood, like now everyone finally knows what has been inside of my mind and body. That is a good feeling.

What’s next?

Playing shows! I’m having a big show in NYC at The Sultan Room on April 27, and then I’m planning some tour dates for the summer. Performing is my passion, and it has been tough to adjust to the new normal in pandemic times. It has made me cherish every single show opportunity I have. Other than that, I have more music and visuals on the way, because even though the album is out, I still haven’t released everything yet. You’ll have to stay tuned.

35

35