Instead of just "weird stories and stupid stuff," the group's new film packs an emotional wallop. Michael Diamond and Adam Horovitz explain how their new project became so meaningful.

“The two of us will do the best we can, because one of us isn’t here,” Michael “Mike D” Diamond declares in the opening minutes of Beastie Boys Story while standing alongside Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz. In the heartfelt new documentary, which premieres on Apple TV+ on Friday (Apr. 24), the pair tells the origin story of their boundary-pushing New York hip-hop trio, while paying tribute to its third member, Adam “MCA” Yauch, whose death in 2012 put an end to their decades-spanning run.

Diamond and Horovitz recently told their story in another medium — the nearly 600-page Beastie Boys Book became a best-seller in late 2018. Soon after, the pair teamed up with another longtime friend, director Spike Jonze, to create a multimedia stage show that would bring the best stories from the book to life in front of a live audience. After a successful run in 2019, the show — part TED Talk, part stand-up routine, with two aging jokesters reflecting on their best pranks and pivotal moments — morphed into the foundation of a documentary, filmed at Kings Theatre in Brooklyn, with Jonze at the helm.

“It was a lot like when we wrote a book called The Secret,” jokes Jonze of the popular self-help text in a statement to Billboard. “The process, actually, was very similar. With both that book and our current project, Adam, Mike and I were able to write while barely speaking, by using the laws of attraction. All we had to do was look at each other from across the room, and the words poured out. It was dizzying in a lot of ways, but that’s exactly why I’ve always loved their band and their music. They’ve always been one of my favorite bands, long before I ever met them. And they probably always will be, too.”

In the documentary, Diamond and Horovitz discuss their memories as teens at New York hardcore shows, the feigned party-boy schtick of their Licensed to Ill days, the disappointment of Paul’s Boutique bombing commercially, and the contrition they now feel over the sexism in their early lyrics. Yauch’s presence as the trio’s creative and intellectual center looms over the documentary; in its climax, Horovitz tears up while recounting the group’s final performance in 2009, a jarring moment of onstage sadness from an artist known for his puckishness.

Yet on a Zoom call in late March — a few weeks into quarantining — Diamond and Horovitz are in a jol mood from separate locations in Los Angeles. Horovitz pokes fun at Diamond’s unkempt hair when he signs on to the video chat (“You’ve got a wonderful, thick, full head of hair, Mike. Flaunt it!,” he crows), and Diamond starts recounting the late ‘80s infomercial for Flowbee, a vacuum attachment for cutting hair (“The time is right for a vacuum hair-cutter thing to come back,” he declares).

They’re thinking about their friends in New York City, cooped up in apartments as the coronavirus pandemic has emptied their beloved city’s streets, and have mixed feelings about Beastie Boys Story becoming available for home streaming while much of the United States is stuck at home (the documentary was scheduled to premiere at South By Southwest 2020 and receive a limited theatrical run prior to the pandemic). And after telling the story of their groundbreaking musical trio in a book, stage show and now a film, they swear there are still a few stories left untold.

“Mike and I are gonna make another book called Funny to Us, of all the stories that no one will probably think that funny, but we think they’re hilarious,” Horovitz says. Diamond nods, and adds in a hushed tone, “Strictly for the heads.”

How did the doc come about, in terms of the conversations that turned the live-show presentation into Spike’s film?

Diamond: Well, it started with the book, because the book was coming out and Adam and I were facing this thing of like, “Oh s–t, we have to go out and promote this book. Are we gonna go sit in a bunch of bookstores with blazers on and try to pretend that we’re real authors? That probably wouldn’t be a good look.” So we started talking to each other [about], what would be a different way that we could present it?

And then we talked with Spike as well at that time — really, I think I was just meeting up with him anyways. That’s the nice thing of having talented people as your friends. We all spun this idea out of, “What if we make it a little bit of a show?” We pick out the places of the book, or the stories within the book, that would basically work as a story as a whole.

The first iterations of the show, we were in New York and Brooklyn and L.A. and San Francisco and London, and that was probably the closest to the book. We really were taking passages of the book and doing a little bit of re-writing to make it work [as a show]. And the response seemed good, so Spike came back to us and was like, “Hey, we should really re-write it so that we can film it properly.” So then the next phase was us getting together with Spike and Jeff Buchanan, our editor, and Amanda [Adelson], our writing partner, and just kind of writing and re-writing every day, with the goal of making it work a little bit better as a show that Spike was gonna film.

As we were filming it, we let the shows run a bit longer — they weren’t perfected as shows, because we knew that we were filming them, but we still thought that that was basically going to be the show. When we first saw the rough cut of the film, Spike already started editing other things into it, because he and Jeff realized that it worked really well as a stage show — but why be limited to just having it be a documentary of that stage show? Why not have the film be its own thing, that has a life of its own, with a trajectory of its own?

Horovitz: That was our idea of what a show was like — just weird stories and stupid stuff, right? We talked to Spike, and he kept pushing us to make it more emotional, bring out more things conducive to a movie, with a story arc and all that stuff.

How long did it take to find that structure?

Diamond: We spent a pretty solid amount of time — from January [2019] until when we first started performing the show to film in Philadelphia in April, that whole period of time — writing and re-writing. And it was like Adam was saying, a back-and-forth, and a little bit of pulling, in a good way. That’s why it was so great working with Spike: We can disagree with him, but we can thoroughly trust him. We can be more comfortable joking around and doing things that are funny to us, and Spike found this role where he kept asking us, “What were you feeling at that time? Why does this need to be in the story? What’s going on here?” Everything had its place.

The documentary is very reflective — less a string of stories, and more of an explanation of how you guys were experiencing at all these different points in your career. It’s interesting to hear that Spike had a big part in conjuring that emotion.

Horovitz: Yeah. When Mike and I wrote the first version of the story that we were first doing the shows on, it was like four hours long, and there was a lot of dumb stuff in it. There was… a talk show in there? All kinds of dumb s–t that we thought was funny but ultimately was, eh, okay. And so Spike, an award-winning writer — allegedly — tried his best to hone the story in. And actually, the finished movie is not what we thought it was gonna be. We didn’t realize that it was gonna be a documentary, just a document of the show that we did. So it was weird watching it the first time, but ultimately I think it’s way better than what it would have been.

What was it like being back onstage?

Horovitz: Um… easy.

Diamond: That part, sadly, was comfortable for us. It’s been our whole lives since we were 18 or 19 years old. But I think what was different for us was, we were used to in between songs joking around with the audience. To be actually conscious of telling a story and not get too tangential, and then also tell a story that — not only with Yauch dying, but this whole journey that we lived through with Yauch — at times would be genuinely emotional for us on the stage, that was definitely a different thing for us, definitely uncharted territory, and not necessarily a comfortable place for us.

How difficult was it for you guys to discuss onstage some of the relationships that had, for one reason or another, faltered over the years? Obviously you talk about former band member Kate Schellenbach leaving and later making amends, but also a large part of the film’s first half is talking about Rick Rubin and Russell Simmons, and some of the things that went wrong in your business relationship.

Horovitz: We’d already really delved into those things when writing the book, so not to say that our feelings were already figured out by then, but we had been thinking about that for a long time.

Diamond: But there were a lot of challenges in there, because we wanted to be honest in terms of reflecting on our own actions about how we dealt with Kate and what it’s like when you’re young and awkward and don’t handle situations well. And with Rick, everybody had a role — Rick had such an important role of being a producer, but that doesn’t mean we need to be with him forever, that doesn’t mean we see eye-to-eye. Or like, with Russell, he had this important role in terms of having this commercial vision, but that didn’t mean that he was looking out for our best interests — he was looking out for his own. So until you’re talking about it and reflecting on it onstage, I guess it brought it to a next level of being real, in a weird way.

Horovitz: And it was also 30 years ago. The hardest part really for us was just talking about Adam Yauch. Being sad is one thing, but when you start talking out loud when you’re sad, that’s hard, for all of us.

The emotional center of the documentary is the discussion of your final performance with Yauch. Did that get easier to talk about on a night-to-night basis, or was it always incredibly raw to get through that moment of each show?

Diamond: I don’t know. I almost feel like it got harder. Because it somehow became more emotionally resonant for us as we did it. We went from a thing of doing these lines onstage to then we… we went into the moment more. It had a life of its own, and there’s no denying it was a very emotional, and a moment of us really missing our friend and partner.

Horovitz: Mike talks a lot about Stanislavski’s Method, you know? And it’s not real unless you feel it, right, Mike?

Diamond: He who knows it feels it.

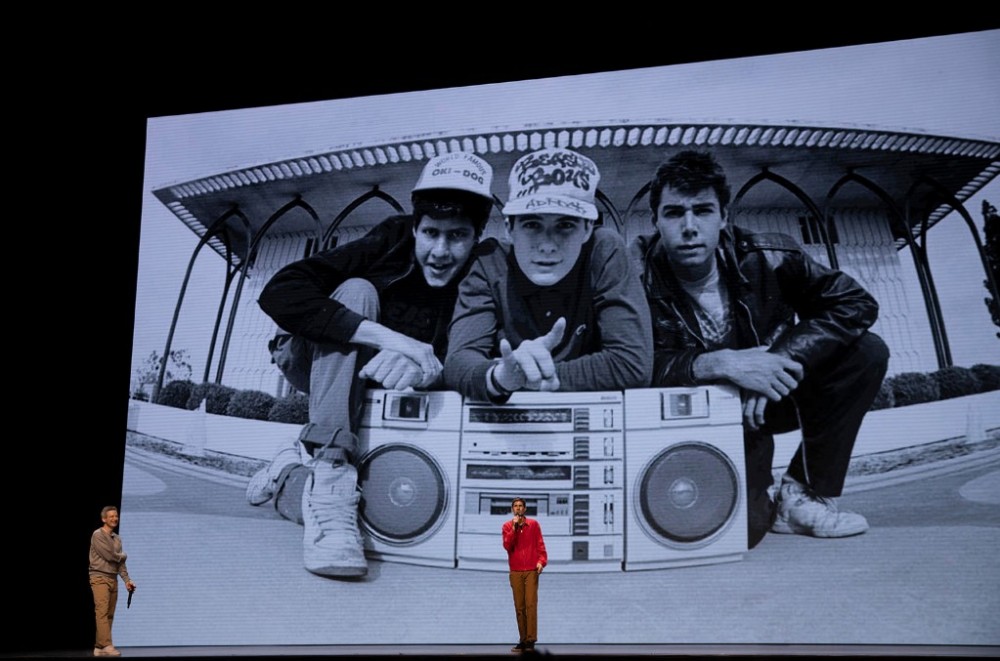

Also translated from the book to the documentary: a reflection on both race and misogyny in hip-hop. You point out the “Sure Shot” lyrics that rail against sexism, but I thought some of the visuals in the documentary — like the photo of you guys as teens in do-rags, then cutting back to you cringing onstage at the photo — drove home some of those evolving dynamics.

Horovitz: Well, let’s first not just limit it to hip-hop. Is that okay? It’s the entire world.

Diamond: Well I would argue — and I think you’re right, Adam — but it’s interesting, because it is the popular form of music. It is this thing where there are people from all over the world who have learned about so many issues and other people’s realities through hip-hop. People are able to present their ideas and their realities and parts of their personalities in a way that I think a lot of other forms of music might not totally allow for that.

Horovitz: I agree, but society informs us all, and informs rappers.

Diamond: And we’re fortunate, right? Here we are, all these decades after the fact of being 19 and being super excited that we met Run-DMC, that we’re starting to make rap music, and at the same time we were dumbasses! We hire this limousine, we go out to this club and we dress up in Puma suits and have do-rags on, and it’s not with any irony at all. Right after doing that, we realized, that’s not us, and that’s not our place to do it. So I don’t know what the answer is, just that we’re fortunate enough that we got to keep going, and hopefully learn some of the lessons along the way.

How much current hip-hop do you guys listen to?

Diamond: I go through phases — sometimes I listen to some stuff, sometimes I get discouraged, sometimes I get encouraged. Ultimately, hip-hop is still our one popular music in the world that constantly reinvents itself. There’s always something looming around the corner that’s going to change the way that everything sounds, and the way we think records are going to be made, even if it seems like it’s a little bit of a long time period until that happens.

Horovitz: I don’t listen to that much new music in general. I listen to the radio, and I guess if I’m listening to music on the radio, I’m listening to rap music. I just want to give a shout-out to [Afro-jazz legend] Manu Dibango right now.

Diamond: Ah yeah, recently passed away.

Horovitz: You hear a song like “New Bell,” and that is such a great song, why not just keep listening to that over and over again? So great.

Diamond: I went back and watched a couple of live clips of Manu Dibango, and they were so, so f–king good.

So the documentary comes out soon on Apple TV+. How did that partnership happen? This is a big get for them as a new streaming service.

Horovitz: Rather than trying to get somebody involved with us first and then make it, we wanted to make it first and have it, and then try to sell it somewhere.

Diamond: And we’ve worked with John Silva, our manager, for a really long time, even longer than we’ve worked with Spike. The nucleus of us, Spike, John, made it, and then were like “Let’s find a distributor.” We met with everybody, and we were lucky that different people were interested in doing it with us. With Apple, they were the ones who came with the biggest ideas. And I guess that’s part of being a new company — they weren’t like, “This is what we do, this is how we do it.” They were the ones who put the most thought into it in their meeting.

And everybody can watch it soon, since it’ll be on a streaming service and everybody’s home.

Diamond: It was a weird, bittersweet thing. Apple did these huge billboards that are right across from the Staples Center, here in downtown L.A. So it was like, “The Lakers are gonna be in the playoffs, the Clippers are gonna be in the playoffs, you’re gonna come out of this arena, tens of thousands of people, and see these billboards for this Beastie Boys Story on Apple TV+!” And now it’s like… maybe once in a while, you might drive by downtown L.A. and see them?

Horovitz: A few cars a day on the highway!

Diamond: I’m definitely missing basketball season a lot right now.

Horovitz: You know, I’m okay with it, to be honest.

Diamond: How are you okay with it, Adam?!

Horovitz: I mean… there’s nothing the Knicks are gonna do in the near future anyway, so…

Diamond: From that perspective, yeah. But I’m missing —

Horovitz: I look at things from a certain perspective, Mike!

How has working on the book, stage show and documentary over the past couple of years changed the relationship between the two of you?

Diamond: It hasn’t. We’re still the same f–king love-hate, can’t wait to slam each other on the couch… I don’t know.

Horovitz: We’ve been really, really close friends for almost 40 years. So it’ll be like [Walter Matthau-George Burns comedy] The Sunshine Boys at some point, but for now we’re really good friends, still.

You’ve spent the last few years completing some very backward-looking art, after spending most of your careers making very forward-looking music. Where do you see yourselves going beyond this point?

Horovitz: Well, I’m just trying to f–king stay alive right now, so. Maybe we can readdress this in a few months.

(Ed. note: This interview has been edited for clarity.)

46

46