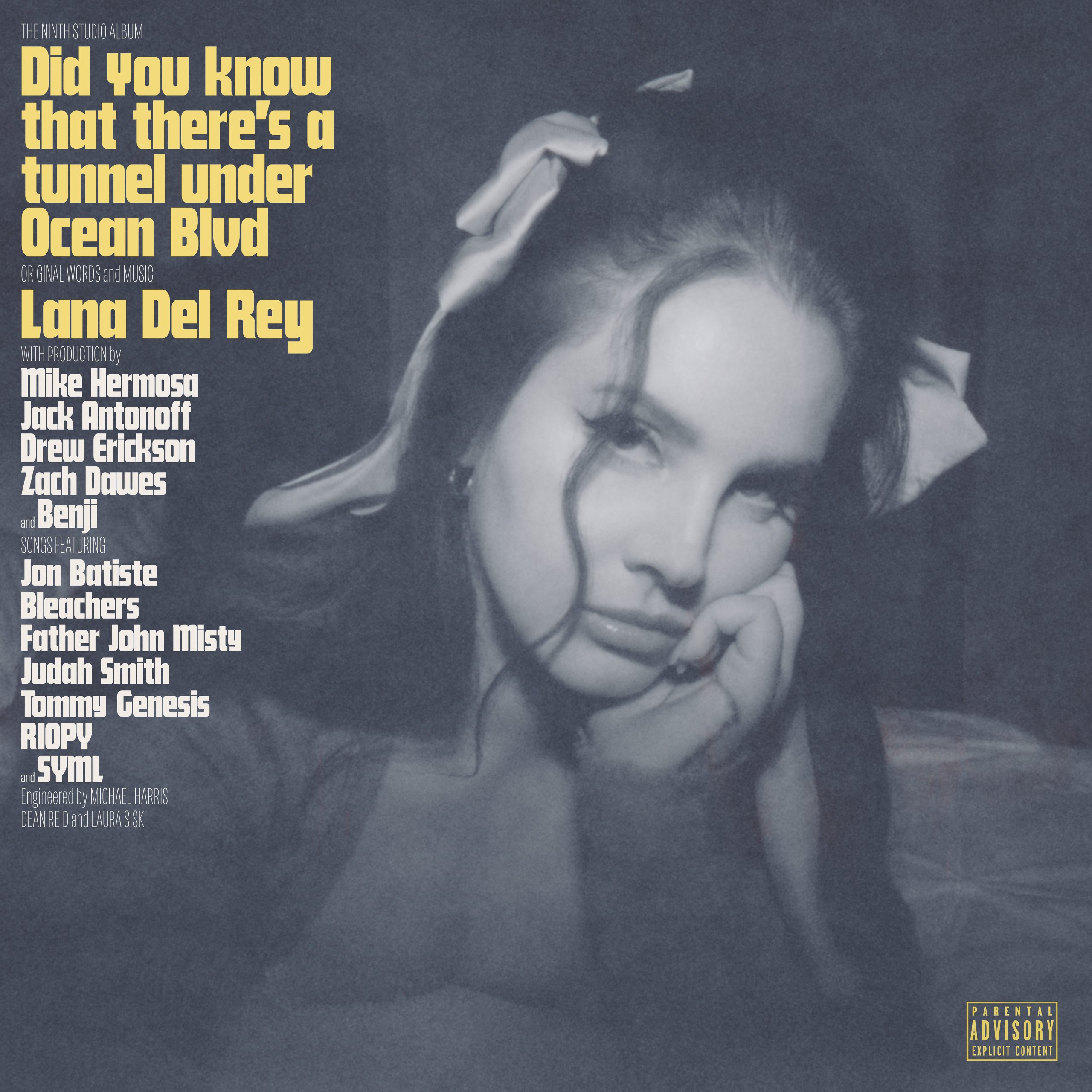

In the age of generational grandstanding, when “nepo babies” break a sweat to deny their indisputable advantages in their parents’ lines of work, it now seems quaint that 10 years ago, Lana Del Rey was controversial for her acute lack of background. Who was this mysterious all-American woman here to croon about blue-collar boys and the Hollywood Hills? How could she sing so knowingly about dive bar romances if she used a pen name? We could handle Lady Gaga, whose rebirth from Stefani Germanotta was cloaked in flank steaks and vaudevillian drama. But in choosing a stage name, the woman raised Lizzy Grant seemed to lose her ability to claim the person she was before her rechristening. Her songs, even in their specificity, were written off as record label retconning, a ghostwriter drafting the heartbreak and torment that would fit on the lips of a woman called Lana Del Rey. Lana Del Rey might not have a family, but Lizzy Grant does, and on her ninth album, Did You Know That There’s A Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd, they’re the centerpiece of her heartbreak.

Opening track “The Grants,” the last single to come out before the album’s release, introduces us to the main characters of Del Rey’s world at the moment: her faith, her aging body, and her bloodline. “My pastor told me when you leave, all you take is your memories,” she sings, her voice drifting upwards as if to direct the song towards the sky. As for her fate, she gestures towards it shakily throughout the album. But whenever she goes, she’s bringing her sister’s child and her grandmother’s smile to the pearly gates with her.

Family and death are twin ghosts haunting Ocean Blvd throughout the album, as if finality is the only constant in her life. On “Kintsugi,” she recounts the last days of her grandmother’s life in predictable beats: tears, laughter, and a singular reference to her boyfriend, Salem’s Jack Donoghue, as a comfort during grief. But more vulnerable, more real, more Lana, more Lizzy, is her alienation while surrounded by her loved ones. “How do my blood relatives know all of these songs,” she asks, genuinely incredulous. Even the 14-year-old can sing “Froggie Came A-Courtin,” yet here she is, the brightest star in the room, standing there wondering who will sing the songs she knows when her time comes.

Ocean Blvd is marked by absence — through death, often, but just as poignantly, through omission. Lana lingers in her grief on “Fingertips,” singing about the death by suicide of her uncle, whose funeral she missed because she was performing for the Prince of Monaco. She wonders aloud if her father, sister, and brother will be by her side in 10 years — that is, if she makes it that long before her DNA atrophies. Where is her mother? She’s a lacuna, an ellipsis in a later verse: “What kind of… was she to say I’d end up in institutions?” Del Rey sings. “What the fuck’s wrong in your head to send me away,” she cries, and suddenly, it’s no wonder she’s having second thoughts about motherhood on the same song. And then, of course, there’s the mouthful of a song title, “Grandfather please stand on the shoulders of my father while he’s deep-sea fishing” — a collaboration with the classical pianist Riopy — which finds her looking for signs that someone is up above, sending her butterflies.

“A&W,” a seven-minute, winding epic, could stand in as a thesis statement for the entire Lana Del Rey project. It starts with Del Rey cartwheeling at nine years old, and ends lightyears away in a strung-out lovelorn spiral. The verses here are whispered, and words blend into each other — Del Rey used a method of meditative automatic singing to write the album — but they sketch out a map of her chaotic, sharpened mind. “Do you really think I give a damn?” she asks, as if her resilience after 10 years of relentless paparazzi alone weren’t enough of an implied answer. She sings with striking frankness about rape culture, madonna-whore complexes, the double standard of aging while female: “Did you know a singer can still be looking like a sidepiece at 33?” She’s used to being the other woman, it seems, but it doesn’t make it hurt any less. And then, about four minutes into the acoustic, piano-driven song, a padded beat drops, then two, until a buzzing backline of bass propels the song into another dimension. Here, we meet “Jimmy,” who smokes cocaine-laced joints as a giddy Del Rey teases, “Your mom called, I told her, you’re fucking up big time.” It’s a journey of a song, but one that effectively draws a straight line from girlhood to being an “American whore”; from being a princess to sleeping in motels; from being Lizzy Grant to becoming Lana Del Rey.

The two halves of “A&W” mirror the construction of the album as a whole: From the wispy piano ballads of Ocean Blvd’s first half to the Auto-Tune and snare drum snaps of its second. In a break from the turn towards Laurel Canyon lullabies she made on Norman Fucking Rockwell!, LDR lets her hair down a bit more here. With the help of frequent collaborator Jack Antonoff (who sneaks in his best Bruce Springsteen impression on the love letter to his fiancée, “Margaret”), she keeps the spaciousness that defined her new sound — the airy emptiness between piano strokes where her voice melts, bends, and retreats — while reintroducing the rhythms that defined her breakout albums. “Fishtail,” with its elongated vowels and breathy repetitions about sadness, feels like Lust For Life Lana born anew, with the confidence to veer off beat and write lyrics like “I wish I could skinny-dip inside your mind.” “Peppers,” which opens with a sample from Tommy Genesis’ “Angelina,” is a proving ground for this combination: She can pull back on the Gatsby-esque spectacle of “Young And Beautiful” and still pack a punch while running her mouth about nothing at all.

On an album that extends far beyond the hour mark, the two interludes feel more like guilty pleasures than necessary additions: The second, from Jon Batiste, follows his duet with Del Rey “Candy Necklace.” Their pairing is natural — they feel like old friends as they laugh about nothing and everything at once. But the first is more inexplicable: A bizarre, grainy phone recording of megachurch pastor Judah Smith, which only highlights the harshness in the tenor of his voice, the volume of his shouting, the intensity in his words. His sermon feels out of place next to the subtlety and sexuality of her lyrics preceding his song — It’s hard to take seriously someone who calls God a “rhino designer” after grooving through the oozing deviance of “A&W.” But the laughter on the recording is a reminder that Lana Del Rey is who she says she is, all the time: She can be a sexed up “American whore” fucking on a hotel floor in one song, and a church girl, giggling in the pews, praying for salvation in the next.

There’s a sense on Ocean Blvd that life is fleeting, crumbling, marked for deprecation from the start. There’s those pesky telomeres on “Fingertips,” a fatal flaw built into the human genome. And then there’s all the small ways she destroys herself — chasing bad romances, running away from anything resembling home. Even the album’s namesake is an homage to the buried: On the album’s title track, she details an actual tunnel closed off to the public, its paths forgotten by the march of time. She thinks about when Harry Nilsson sings, “Don’t forget me.” The way the song is written, she gets to sing, “Don’t forget me,” too. There’s a wistful irony in hearing those words from someone so unbelievably known, at least in the public eye. But she doesn’t care if the public remembers her. She just wants her grandfather to stand on her father’s shoulders and send her three white butterflies, as if to say, “I remember.”

84

84