CW: spoilers and discussions of sexual assault, homophobia, poverty

When I think about Euphoria, I think about glittery eye make up and how badly I want to be Zendaya. When I think about Riverdale, I think about Madelaine Petsch’s perfect red lipstick and KJ Apa’s abs.

And though these are “high school dramas,” I don’t expect them to actually represent the high school experience. And even when they tackle real issues that real teens face, I don’t look at them and see real life.

Grand Army is different.

The first scene sets up exactly what will follow: deftly danced chaos. The camera spins from girls in the locker room singing, girls around the mirror making Instagram videos, and a girl unflinchingly pulling a condom out of a friend in a bathroom stall. Though the show hones its focus, it never loses the artful chaos of that opening scene — the shifting focus, the intimately juxtaposed displays of teen carefulness and carelessness all in one place.

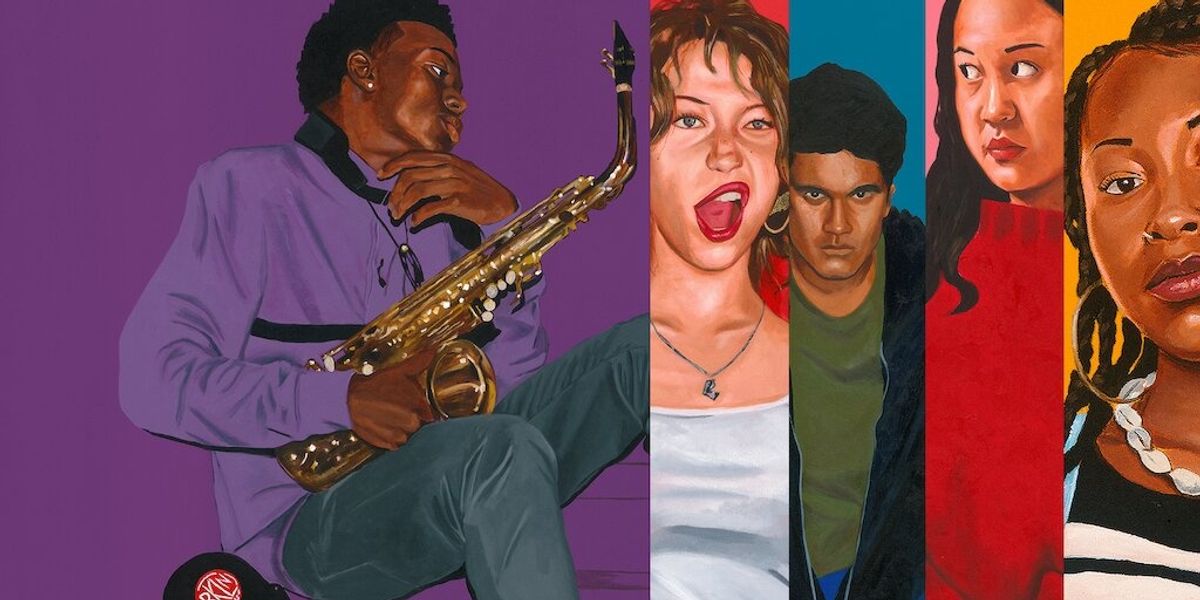

Grand Army, a new Netflix Original based on Slut: The Play (2013) by Katie Cappiello, follows five teens attending the titular public high school in New York City: Joey (Odessa A’zion), an outspoken feminist who is sexually assaulted in the middle of the series; Dom (Odley Jean), a self-described queen of side-hustles trying to balance the advent of her first relationship with supporting her family; Jay (Maliq Johnson), a talented musician who is impacted by the racism of the school district; Sid (Amir Bageria), a teen struggling with the competing desires of fitting in at school and standing out in his Harvard application essay; and Leila (Amalia Yoo), a freshman struggling with reconciling her Chinese ethnicity and her adopted Jewish parents while trying to fit in.

Throughout the nine-episode season, the lives of these teens are constantly shifting across an array of challenges and traumas. Grand Army doesn’t shy away from any topic: institutionalized racism, poverty, sexual assault.

However, many early reviews called the series bloated, straining under the weight of its admittedly heavy storylines. But here’s what they were missing and what Grand Army understands about high school that other shows don’t: Life doesn’t stop so you can process it. High school is a relentless, unglamorous mixture of both trauma and tenderness, all happening all at once. The characters in Grand Army are never not carrying their emotional burdens, but they’re so much more than them, too.

What makes Grand Army different from shows like Riverdale, Euphoria, and even 13 Reasons Why is the trust that it gives its audience. Though its protagonists might not see all the nuanced factors at play in their actions, the writers do. As a social issue drama, it doesn’t give the characters all the answers or leave them spiraling in the mess of their own bad decision-making. In Grand Army, the world is unfair and hard, but the show trusts its characters to make it out okay.

Real Representation

Grand Army starts with a bomb threat … then promptly moves on. The act of terrorism serves as a catalyst to unearth the underlying issues of over-policing in public schools, racism, and the urgency of being a teenager—thinking everything has to matter, especially you. Most of the social and personal issues arise as part of life in the city, or unfold as they only could in New York.

There’s an element of self-destruction inherent in adolescence. Yet, most high school dramas overplay the spirals of poor decision-making and meet them with either shallow or melodramatic consequences (I had to stop watching Riverdale in the episode Archie chooses to go to jail … like, what?). Instead, Grand Army finds its footing on a middle path, on which the lives of its characters are impacted by personal and external decisions.

Jay, for example, finds his careless act on “Bomb Day” leading to the prolonged suspension of his best friend due to the exaggerated consequences of zero-tolerence policies and systemic racism. His own carefree nature is curbed by the reality of how the system treats Black boys, shifting his priorities in light of a world that doesn’t try to understand him.

The nuance of the situation is not fully understood by Jay either, but he spends the show trying to unravel and understand it. This is also true of Dom, who wants to be a therapist but cannot afford therapy herself, as she confesses to a group of affluent teens she meets on one of her many “side hustles.” Her story is full of roadblocks that she tries to navigate, predictably stumbling and self-destructing.

But the focus is always outward. Grand Army is emphatically tackling larger societal problems through the lens of its characters, rather than portraying them as individual, isolated problems. Shows like Euphoria and 13 Reasons Why claim to do the same, but they don’t do so broadly enough.

All claims that Grand Army isn’t nuanced enough are missing the point. Grand Army tackles the scope of teen trauma and how it’s relentless and often compounded for vulnerable groups.

What’s overwhelming about Grand Army–what makes it representative–is the focus on marginalized identity. This is not about chiseled white boys making things harder on themselves; it’s about wrestling with how the world treats women, queer people, immigrants, and Black people, even as young kids teeming with hope and potential.

Not a Glamorization of Trauma

The most commendable thing about Grand Army is how it doesn’t minimize trauma, but it also doesn’t glamorize it. Whether it’s the dubious morals of Euphoria characters and their toxic but super hot relationships — reminiscent of its blueprint, Skins — it’s a show about teens that comes with a disclaimer for young audiences.

While Grand Army isn’t fun-for-the-whole-family by any means, it feels as though it’s speaking to its demographic, not about them while they’re in the same room. While fun to watch, it’s too easy to take bad advice from shows like Euphoria or Riverdale, which can be okay — but not every show needs to be didactic. In contrast, Grand Army doesn’t let its characters off so easily — without feeling like a lecture.

This is especially hard when portraying the issues of marginalized characters. It is easy for a show to become “trauma p-rn,” to reduce its marginalized characters to only their pain. This out is not available here. With all the characters belonging to one or more underrepresented communities, the show has no choice but to make them nuanced and complex.

Leila is one of the most complex characters in the show — mostly because she’s awful. While the audience can empathize with some of her internal conflict, her laughable selfishness becomes her defining character trait. Grand Army doesn’t let marginalized identity be a stand-in for personality. Yes, the characters are shaped by their backgrounds, but they are not only that. They are allowed to be sometimes good, sometimes valid, and sometimes really not.

This complex portrayal feels so timely now, when community belonging or allyship can become a person’s brand in insidious ways. The group of boys who begin as Joey’s friends, who she calls her “woke boys” when they stand with her during her protest against the dress code, saying to each other, “Dude, you don’t have to explain to me what misogyny is,” end up being some of the worst characters in the show.

There’s an agency in this, an actionable truth: Teenagers have an admirable elasticity and resilience when it comes to healing, yes, but they also have the power and agency to do the harm and commit the violence, rather than being helpless to it or only enacting shallow drama — some more than others. Everyone is more than they appear, Grand Army says. And sometimes they’re not what they appear at all.

Not an Oversexualization of Teens, Either

Here’s what not to expect: wide angle outfit shots or slow motion close ups of locker room abs. In fact, I was seven episodes deep when I realized I barely knew what the character’s bodies looked like — at least not in the way I was used to on teen TV. There’s an element of high school dramas that’s aspirational. You wish you could look like the characters, so maybe you try in small ways, but you know most likely you will not pull up to the first period looking like an Instagram model. At least not most of us, and not in high school.

Grand Army plays the camera close to the face, reserving its full body shots for when they matter. This directorial precision allows the story to be at the forefront: You see what the story needs you to see, not what will make for Instagram trends or a make-up Emmy.

When Joey walks down the halls in a semi-sheer “Free The Nipple” tank top to stares and wolf whistles, this isn’t a gratuitous aesthetic display; it’s a nuanced commentary on how her attempt to desexualize the body makes her the subject of more sexualization and speculation, even from the people who claim to “get it.” It’s also a stunning juxtaposition with a later scene, wherein a similar shot shows Joey met with the same stares and speculation, yet this time after her sexual assault, now clad in oversized clothing and holding her head down.

The frequent facial-close ups serve to emphasize the emotions in the show. The emotional power of the show is carried by the heartwrenching acting of the mostly new-comer cast. How many times did I get chills at Jay’s watering eyes, Dom’s hesitant vulnerability, Joey’s defeated gaze?

The intentional camera work allows the acting to be the focus, not the actors. Grand Army doesn’t rely on sensational aesthetic pleasures. Everything is a vehicle to the story, not a future Instagram promo or a flashy reel of stills.

The Details Matter:

This is not to say the aesthetic choices aren’t smart and indicative of each character. When so much of the show is about perception and bodily trauma, the details are smart and specific. From Leila’s Brandy Melville cardigan — she’s the type — to Joey’s scribbled-on converse, the wardrobe may not be a theater of Instagram-model outfits, but it’s still intentional.

Every other detail is equally attended to. From the actually good college essay upon which Sid’s storyline hinges (with a demographic for whom the college process is a recent wound or an upcoming horror, the usual dubious Netflix college timelines are super distracting) to the scenes of characters Zillowing the apartment they’re going to a party at, so much is bubbling under the surface.

Here’s why it works: You can tell the show trusts its audience to know what’s underneath the surface action. It’s a head nod, a wink, an acknowledgement of understanding. With a generation of activism and Instagram infographics, Grand Army understands that what Gen Z audiences want to see are their emotional realities–people who look like them experiencing the things they feel. The audience gets that the world is hard to live in, and the show gets it too.

It’s Not All Bad:

But it’s not all trauma all the time. Though some episodes were heavier than others, it wasn’t an untenable watching experience. I was never bogged down by its weight.

This is a unique experience. Watching Riverdale usually makes me pause to take a breather from its saccharine sensuality and melodrama. Each episode of Euphoria can be overwhelmingly dark. But because of the shifting story lines, each of which share almost equal screen time, Grand Army achieves a refreshing balance.

The moments of lightness don’t feel gratuitous either. It’s not a party for a party’s sake, a romance for indulgence alone — everything adds to the story without feeling contrived. From Dom’s budding relationship with the disarmingly sweet John Ellis (inarguably the best character in the show) to the unexpected tenderness between her and Joey; to the misguided sweetness of Jay’s efforts to help Owen; to Sid’s relationship with his sister, Meera, I am as equally invested in the healing as I am the hurt.

This is not a show of vicarious thrills. Maybe because it’s an adaptation of a social-issue play, Grand Army is adamantly concerned with telling specific, representative stories.

What makes shows like Riverdale and Euphoria work is that you get invested in the characters — their gorgeousness, their carelessness, their drama — and you’d watch them do even the most unrealistic things. What makes Grand Army work is its focus and specificity, the heartbreaking reality, tied together with tenderness and offering hope for the future, with a little time and a lot of work.

With such a large scope, it is easy to understand the concerns around the show. But just like high school, sometimes you have the answers, sometimes you don’t, and sometimes there isn’t one. And so Grand Army offers a realistic, ultimately forgiving portrait of its flawed characters as they try to find that nuance for themselves.

66

66