In The Number Ones, I’m reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart’s beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

Britney Spears said no. That’s a key part of the story behind “Umbrella,” the gargantuan hit that took Rihanna out of the realm of mere pop stardom and up to the global-icon level. But you can’t blame Britney Spears, herself a global icon, for missing the opportunity. There’s no real evidence that Britney ever even heard the “Umbrella” demo.

The three songwriters who put “Umbrella” together — Terius “The-Dream” Nash, Christopher “Tricky” Stewart, and Thaddis “Kuk” Harrell — had already worked with Britney Spears once. At the time, Britney was at the deepest depths of her dark period, and she needed a hit. The writers knew that they had a hit, and they wanted to give it to her. They submitted the track to Britney’s management, but Jive Records, Britney’s label, said that she already had enough songs for her 2007 album Blackout. So Rihanna got “Umbrella” instead, and “Umbrella” helped turn Rihanna into the Rihanna that we know now.

Britney Spears ultimately made many more hits. She’s already been in this column once, and she’ll be back more times, but none of her later hits conquered the world in the way that “Umbrella” did. So it’s worth wondering: How would “Umbrella” sound if it had been Britney Spears’ comeback single? Britney’s “Umbrella” would’ve been hungrier than Rihanna’s. It might’ve been darker. It might’ve also been slighter. Maybe the song would’ve taken Britney to even higher heights, or maybe it would’ve been overshadowed by the chaos of her public image and her personal life. We’ll never know.

Instead, “Umbrella” became one of those perfect-storm songs. “Umbrella” topped charts all over the world. It became a cultural touchstone, an inescapable mantra. In this column’s commenting community, there are people who claim that they’ve never heard some of the songs that have appeared in this space. I don’t foresee that happening today. “Umbrella” wasn’t just a song; it was a cultural force that could not be denied. If you somehow avoided “Umbrella,” it was because you wanted to avoid “Umbrella.” Even then, I don’t see how you could’ve done it.

I didn’t like “Umbrella” much at first. I wrote the Pitchfork review for Rihanna’s Good Girl Gone Bad album — a great record that I only slightly underrated. At the time, though, “Umbrella” didn’t work for me. Rihanna’s voice sounded mechanistic and almost oppressive, and I couldn’t see why she was the person singing this song that was ostensibly all about comforting someone, about giving someone refuge. I wrote that “Umbrella” was “uncompelling event-pop,” and I blamed “the disconnect between Rihanna’s cold, clinical delivery and the comforting warmth of the lyrics.” But that was a feature, not a bug. Now, years later, that contrast seems key to the enduring power of “Umbrella.” The song presents us with a Rihanna who’s both caring and aloof, warm and icy. Rihanna was already famous and successful, but “Umbrella” was the song that made her.

“Umbrella” started off as a free drum loop on Apple’s GarageBand program, the 21st-century equivalent of a Casio preset. One day, Kuk Harrell was messing around on GarageBand, trying to teach himself the program, when he found an itchy, lurching drum track known as “Vintage Funk Kit 03.”

By this point, Kuk Harrell had been in the music business for a long time. He’d grown up in it. Harrell and his cousin Tricky Stewart were raised in and around Chicago, where Stewart’s father owned an advertising agency and wrote jingles for commercials. Sometimes, the kids of the family would sing on those jingles. Eventually, the kids started writing jingles themselves. Harrell and Stewart credit their time in the jingle-writing business as key preparation for the larger pop world. As jingle writers, the kids couldn’t be precious about their art. They had to just keep cranking out new hooks. It was good practice.

Kuk Harrell eventually moved to Los Angeles, where he worked as a session singer and drummer, and where he did occasional production work for early-’90s R&B acts like Immature and Chanté Moore. In 2004, Harrell moved to Atlanta, where Tricky Stewart had started a production company called RedZone Entertainment.

Tricky Stewart was a prodigy who played tons of instruments as a kid and who once wanted to become a session drummer. Tricky learned production from his older brother Laney Wilson, who produced for people like former Number Ones artist Karyn White. While he was still in high school, Tricky started producing for artists like BlackGirl and former Guy singer Aaron Hall. In 1994, Tricky met LA Reid, and he started RedZone Entertainment with investment money from Reid.

Tricky Stewart kept busy doing production through the second half of the ’90s, working with the Braxtons and Sam Salter and Brownstone and former Number Ones artists 98 Degrees. But Tricky Stewart didn’t make an actual hit until 1999, when he produced the Miami rapper JT Money’s biggest song “Who Dat,” a chant-along banger with a cool Face/Off-riffing video. (“Who Dat” peaked at #5. It’s an 8.) A year later, Stewart also produced and co-wrote “Case Of The Ex,” a #2 hit for the former Number Ones artist Mýa. (That one is a 9.)

While RedZone was getting going, the young songwriter Terius Nash met Laney Stewart and started working with him, eventually earning a position in the RedZone machine. Nash was known as The-Dream — no, I don’t understand the hyphen, either — and he got his break as a songwriter for former Number Ones artists B2K. The RedZone team worked on some of the tracks from Britney Spears’ 2003 album In The Zone, and Tricky Stewart and The-Dream were two of the credited songwriters on Britney’s Madonna collaboration “Me Against The Music,” which peaked at #35.

By 2007, it had been a while since the RedZone team had made a major hit. They needed something. The-Dream, in particular, was desperate. He later told Genius, “I was just in a place in life where I was checking for money, making sure I could get to the studio to write another record. It was just a weird space to say, ‘Write a fuckin’ hit, just write a hit. Stop playing around and just write. You know what a hit sounds like.’” When The-Dream heard Kuk Harrell messing around with that GarageBand drum loop, he immediately felt inspired. In a 2007 interview, The-Dream told Blender the whole story: “I’m like, ‘Oh, my God, what is that beat?’ Then Tricky starts putting some chords over it, and immediately the word popped into my head: umbrella. I ran over to the vocal booth and started singing.”

Based on that beat, The-Dream and Tricky Stewart almost freestyled “Umbrella.” The song practically came together in real time. The-Dream demanded to start recording his vocals when Stewart was still setting the studio up. He had things in his head, and he had to get them out: “I maybe had to go back and change four words but I sung it from the top to the end, exactly as is, how you hear the song today, right now.”

You can almost tell that The-Dream’s “Umbrella” lyrics were improvised. “Umbrella” is a song of support and friendship. The narrator promises to help someone else out when things are difficult; the umbrella of the title is an image of shelter and refuge. Not all of the metaphors in “Umbrella” are that resonant. Consider: “In the dark, you can’t see shiny cars/ And that’s when you need me there.” That’s clunky as hell. The phrase “you’re part of my entity, here for infinity” is oddly poetic, but it’s also practically gibberish. In the context of the towering “Umbrella” hook, though, those lines just glide past. The-Dream’s bridge is almost as triumphant as the chorus: “So gonna let the rain pour! I’ll be all you need and more!”

You can hear practically all of “Umbrella” in the demo that The-Dream recorded on that day. On the demo, Tricky Stewart’s synths sound cheaper, but they still swirl and pound, gathering force until they sound something like power-ballad guitar chords on the chorus. The song’s echoing hook is already fully intact. The-Dream says that the “ella, ella, ella” bit was a workaround. He wanted to use an echo effect, but he also wanted to get the vocal recorded before ProTools crashed: “Everyone who runs ProTools and understands this is you have the option of certain plugins you want to use before your computer actually slows down and you can’t use it anymore. The reverb one was just one that I said I’m not going to use. Instead, I would sing those lines repetitively myself to actually fill that thing in.” The-Dream built a whole songwriting style out of that workaround.

In that Blender interview, The-Dream says that he played his “Umbrella” demo for his then-wife, the R&B singer Nivea, that night. (Nivea’s highest-charting single is “Don’t Mess With My Man,” a 2002 collaboration with Jagged Edge’s Brian and Brandon Casey. That one peaked at #8; it’s a 7.) When she heard the song, Nivea started crying. Then, she told him, “Boy, you done did it now! Now, who’s gonna sing this?” It was a good question.

When Britney Spears’ label turned “Umbrella” down, RedZone started shopping the song around to different singers. They got a lot of interest. Maybe Britney’s people couldn’t envision it, but most of the people who heard the “Umbrella” demo understood that the song was a hit. Tricky Stewart’s brother Mark worked as his manager, and he took the song around to different singers. Mary J. Blige, an artist who’s been in this column once, wanted “Umbrella,” and you have to imagine that she would’ve killed it. But Stewart also sent the track to LA Reid, who sent it to Rihanna.

In 2007, Rihanna was on her grind, getting ready to release her third album in three years. Rihanna had been to #1 with “SOS,” and she’d scored a handful of other major hits: “Pon De Replay,” “Unfaithful,” “Break It Off.” But Rihanna didn’t really have a set identity yet. Rihanna told Blender, “When the demo first started playing, I was like, ‘This is interesting, this is weird.’ But the song kept getting better. I listened to it over and over.” Rihanna told LA Reid that she wanted to record the song the very next day. It wasn’t that easy.

The RedZone Entertainment people ultimately had to decide whether to give the song to Rihanna or Mary J. Blige. When Rihanna heard that Blige wanted the song, she thought that she was out of the running: “Who wouldn’t want Mary J. to sing their record?” Rihanna’s manager kept asking RedZone about the song, and then LA Reid stepped in and “made the producers an offer they couldn’t refuse,” in his own words. Mark Stewart says that the decision wasn’t anything so dramatic. Rihanna was just starting up an album cycle, while Mary J. Blige was not. In any case, Rihanna got the song.

It took me so long to understand what Rihanna does on “Umbrella.” For years, I thought she was cold and robotic, disconnected from a song that’s all about visceral connection. Today, though, the thing that I hear in Rihanna’s voice is strength. Rihanna was never a vocal virtuoso, and a vocal virtuoso could certainly go crazy on “Umbrella.” But Rihanna brings presence. Rihanna’s superpower has always been her absolute coolness, her overwhelming confidence. On “Umbrella,” she’s taking all that self-assured power and telling you that she’ll always be there for you. The effect is powerful.

“Umbrella” isn’t necessarily a romantic song, though you could hear it that way if you wanted. It’s a song about protection, about keeping someone safe from harm. Rihanna brings all of that. Rihanna is probably the sexiest singer of her generation, but she doesn’t rely on that sexiness with “Umbrella.” On the bridge, she even manages to belt out the phrase “baby, come into me” without making it sound like innuendo.

I’ve warmed to “Umbrella” a whole lot over the years, but there’s one thing about the record that still drives me absolutely nuts: What the fuck is Jay-Z doing on that song? During his temporary quasi-retirement from rapping, Jay worked as president of Def Jam and signed Rihanna, so they obviously had a connection. (There were also all those rumors about Jay cheating on Beyoncé with Rihanna.) Near the end of 2006, Jay had ended his fake retirement and released the boring, indulgent executive-rap comeback Kingdom Come, possibly the worst album of his whole career. (Lead single “Show Me What You Got” peaked at #8. It’s a 5.) So Jay was back to rapping, but he did not sound invested in the process.

My theory: Jay-Z knew that “Umbrella” was a hit, and he wanted to be a part of it. This was also the point where it seemed like an event whenever Jay rapped, and Jay’s opening verse might’ve helped bring some attention to “Umbrella.” The decision to put Jay on the track seems to be more about branding than about the song itself. Jay-Z adds nothing to “Umbrella.” Instead, he detracts. Jay could not possibly sound less committed to his verse. “Umbrella” is a song about looking up for someone else, but Jay’s lines are all about how cool he is. That works on a track like Beyoncé’s “Crazy In Love,” where Jay essentially casts himself as the object of the song’s affections. On “Umbrella,” though, it misses the point completely.

There are other differences, too. Jay-Z’s “Crazy In Love” verse is great; his “Umbrella” verse is trash. People love to talk about Jay’s Rain Man state — the proverbial trance that he goes into in the studio, hearing a beat and figuring out entire verses in his head. But Jay’s “Umbrella” verse tries to make a pun out of the Rain Man thing, and then the entire rest of the verse is indolent weather-related wordplay. There’s no clouds in Jay’s stones. He hydroplanes in the bank. He flies higher than weather and stacks chips for a rainy day. He also refers to Rihanna as “Little Miss Sunshine.” I hate it so much.

At least Jay-Z’s “Umbrella” verse is short. At least it cuts off just as the song itself begins. “Umbrella,” incidentally, marks the third time that Jay rapped on a female pop star’s #1 hit, after “Crazy In Love” and Mariah Carey’s “Heartbreaker.” Jay will eventually appear in this column as lead artist, but he’ll need help from a different female pop star to get there. A few months after “Umbrella” hit #1, Jay stepped down from his Def Jam position, though he’s still very involved in Rihanna’s career today.

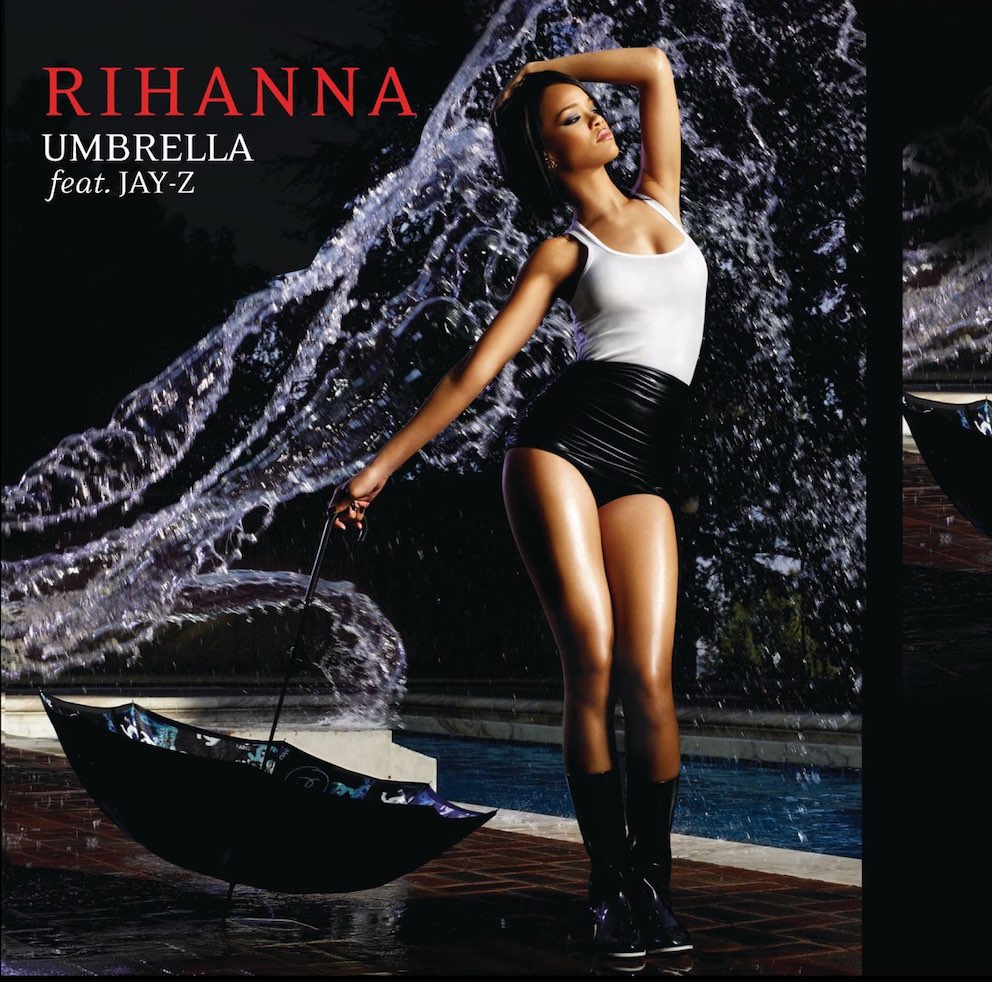

Chris Applebaum, the director who’d already shot Rihanna’s “SOS” video, came back for the “Umbrella” clip. It’s mostly a simple video — Rihanna and different dancers standing out against a black background with occasional rain effects and terrible water-splashing CGI. But Rihanna looks like a star. The video debuted Rihanna’s new hairdo, a severe and angular cut that made her look positively futuristic. In every close-up shot, her eyes burn holes in the camera.

“Umbrella” quickly became a global smash. The song became a bit of a cute news story. In certain countries — the UK, New Zealand, Romania — catastrophic rainfalls arrived as “Umbrella” raced up the charts. I’m sure those stories helped the song, but the song didn’t need the help. In the US, “Umbrella” absolutely dominated the summer of 2007, and it hit #1 the week after Rihanna’s Good Girl Gone Bad album came out. More hits quickly followed.

Rihanna’s immediate “Umbrella” follow-up was “Shut Up And Drive,” a new-wave rocker that might be the best track that Evan Rogers and Carl Sturken, the two producers who discovered Rihanna, ever made for her. “Shut Up And Drive” samples New Order but sounds more like the Cars, and it peaked at #15. After that, Rihanna got to #7 with “Hate That I Love You,” a despondent duet with songwriter and former Number Ones artist Ne-Yo. (“Hate That I Love You” is a 7.)

My favorite Good Girl Gone Bad single was the next one. “Don’t Stop The Music,” a full-on Euro-club banger built on StarGate’s Michael Jackson sample, anticipated and maybe even influenced the EDM boom. Rihanna has a lot of almighty dance songs, and “Don’t Stop The Music” is one of the best. (That song peaked at #3. It’s a 10.) Those Good Girl Gone Bad singles were all different — four songs, four styles. But all four were big hits, and all four sounded like Rihanna. She brought the same presence, the same ineffable gravitas, to all of them.

Those hits were monsters, but the initial knock on Rihanna was that she was a singles artist, that the albums were disposable. Even after four big singles, Good Girl Gone Bad only sold a million copies in the US in its first year. One year after its release, Def Jam gave the album a deluxe reissue with a few added-on tracks, and a couple of those tracks will eventually appear in this column. Partly thanks to the endurance of “Umbrella” in the streaming era, Good Girl Gone Bad has now gone platinum six times over.

“Umbrella” had plenty of other long-tail effects. The-Dream, Tricky Stewart, and Kuk Harrell soon notched up more hits, including a few songs that sounded more than a little like “Umbrella”; their work will appear in this column again. In the wake of the “Umbrella” wave, The-Dream signed to Def Jam as a solo artist, and he’s released a bunch of moderately popular albums on that label. (The-Dream’s highest-charting single is his 2007 debut, the Fabolous collab “Shawty Is Da Shit,” which has a lot of those “Umbrella”-style echo-stutter vocals and which peaked at #17.)

“Umbrella” made Rihanna tremendously famous. Around the same time that the song took off, she started dating Chris Brown, a singer who’s already been in this column once and who will be back. Brown recorded his own “Umbrella” remix called “Cinderella,” which was all over R&B radio that summer.

In 2008, I saw Rihanna on Kanye West’s Glow In The Dark tour at Madison Square Garden. She ended her set with “Umbrella,” and then Chris Brown came out to sing his version of the song with her. The crowd at the Garden immediately lost its mind. Kids were levitating. People really invested themselves emotionally in that Chris Brown/Rihanna relationship. You probably don’t need me to tell you that it ended badly. Chris Brown severely beat Rihanna on the night before the 2009 Grammys, and photos of a battered Rihanna leaked online. We’ll have to get deeper into that story in future columns. It won’t be fun.

Rihanna’s career has proven to be a whole lot bigger than “Umbrella,” but “Umbrella” still feels like Rihanna’s signature song, her defining statement. Last month, Rihanna sang “Umbrella” at her Super Bowl Halftime Show, and I was mildly surprised that she didn’t use the song as her big closer. “Umbrella” might still have been the climax of the set — Rihanna, pregnant in a blood-red cape, performing the song on a floating platform while fireworks erupted all around the stadium and Jay-Z watched from the sidelines. The week after the Super Bowl, “Umbrella” returned to the Hot 100, sitting at #37. A few other Rihanna songs reentered the Hot 100 that week, but none of them did as well as “Umbrella.”

During that Halftime Show set, Rihanna didn’t sing any songs that were older than “Umbrella.” It’s almost like she recognized that “Umbrella” marked the moment when she entered some new tier of pop stardom, that it immediately eclipsed everything she’d done beforehand. “Umbrella” took Rihanna to new heights, and she maintained those heights for a long time. We will see much more of Rihanna in this column.

GRADE: 9/10

44

44