This article contains spoilers for “The Witch.”

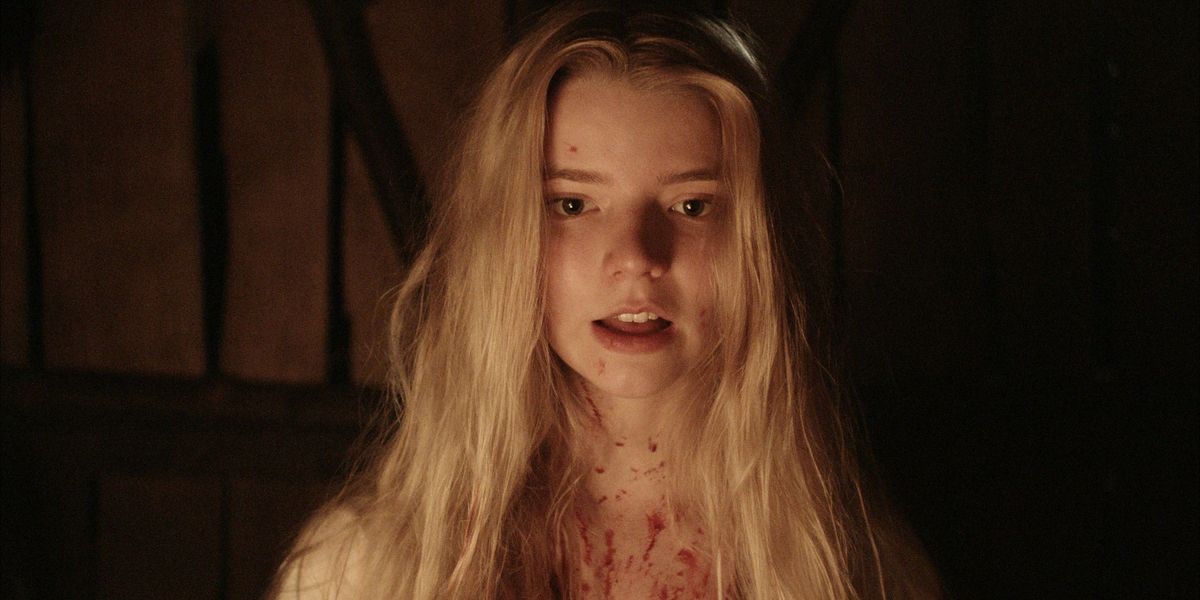

At the end of Robert Eggers’ movie The Witch, the main character—a young girl named Thomasin—removes her bloodstained clothes and wanders into the woods, following what appears to be an iteration of the devil who’s been masquerading as the family goat.

She stumbles upon a circle of other naked women, convulsing and dancing around a fire. They start to levitate. So does Thomasin. In the film’s final frames, her face breaks out into an expression of ecstasy.

This final scene is a marked departure from the rest of the film, which is mostly a story of Puritanical fear and tragedy. Cast out from the church, Thomasin’s family tries to make their way in the woods, but of course things go very, very wrong, and Thomasin and her burgeoning sexuality are blamed for most of what happens. By the end of the film, she has nowhere else to go; her only choice is between Satan’s rites, a life of unbearable trauma and lies, or death. So why has the movie been read as a feminist triumph? And should it be?

The answer lies in an old tradition of subversion. At the end of the film, Thomasin becomes a witch, the sort of powerful, untamed creature of the woods that Christianity and Puritanical culture has always feared—and blamed. The same progression has been followed by pagans and various Satan worshipers, all of whom were damned as infidels by traditional Christian beliefs, forming an enduring stigma that hasn’t gone away but finding redemption in owning that stigma.

The witch woman archetype appeals because it completely shatters Puritanical norms and their offshoots, creating room for an ugliness, complexity, and aggressive liberation that is often not afforded to women, even as feminism grows and changes. In a world that demonizes and restricts noncompliant bodies, where women constantly face assault, and where marginalized groups are finally beginning to lash out at oppressive, age-old colonial forces, witchcraft is appealing because it breaks down the illusion that remaining in the system is moral, nice, or proper. Sometimes true kindness has fangs. Sometimes liberation means you need to use magic, or violence, or a brew of both. But it always comes at a price.

The Witch | Official Trailer HD | A24

www.youtube.com

Female Monsters of the Past

Our culture’s fear and distrust of women is ingrained in one of our oldest stories, beginning with the moment Eve took the apple from Satan. In some interpretations, feminism begins before even that. As the story goes, Adam actually had a first wife in the Garden of Eden—a woman named Lilith. As the folktale goes, Lilith refused to submit to Adam’s sexual desires and so was cast out of paradise. In the horror stories, she gained magic powers, married the devil and started stealing and murdering babies. (Interestingly, that archetype of the child-murdering woman can be seen in modern myths like the story of La Llorona, Hansel and Gretel, and dozens of urban legends from across the world about women who will chase and kill children).

But in reinterpretations of this folktale dating back to the 19th century, Lilith has often been viewed as the first feminist. A woman who didn’t fit into paradise, who would not compromise her sexual desires for a man, and who found magic and liberation in her demonized status, Lilith inspired fields of other myths and legends.

Sexually deviant, long-haired women who live freely and refuse to become mothers and wives have always been taboo. They live in our imagination as everything from fearful banshees to the v*gina dentata.

Feminist Occultism in America: The Rise, Fall, and Reemergence

By the mid-20th century, Puritanical beliefs had metamorphosed into modern, media-driven ideas like slut-shaming, beauty bias, and ageism, and consequently witchcraft and Satanism reentered the public’s consciousness. As feminism rose parallel to these ideas, women and marginalized people began to reclaim the archetype of the witch of the woods, tracing its roots through history and realizing that for many, witchcraft and occultism was a way of achieving power, of being liberated from a system that sought to control and subjugate them.

Similarly, the Satanic Temple generated an offshoot called satanic feminism, which connects back to the Garden of Eden story. If Satan gave Eve the apple of knowledge, then he (or she) was a kind of feminist liberator, saving Eve from patriarchy’s clutches, these thinkers proposed. Occult theosophists like Helena Blavatsky wrote sympathetically about the devil, counter-reading the Bible’s fear of Satan as a way for the Bible to preach fear of all non-compliant “others.”

“We still have that part of our cultural memory,” says Jex Blackmore, a Satanic activist and former spokesperson for the Satanic Temple, in an interview about why she supports Eggers’ The Witch. “[But] the witch wasn’t really created by anyone besides the dominant power structure, which was the church and a few idiocratic governments.” Like witchcraft, satanism has a long history of being intertwined with feminism and anti-oppression work. “As Satanists, we are ever mindful of the plight of women and outsiders throughout history who suffered under the hammer of theocracy and yet fought to empower themselves,” Blackmore said. “We question the authority of the state, as it has proven to be violent, racist, sexist, and classist, and embrace satanism on our own terms as a catalyst for political and social change,” writes Blackmore in Bitch Media. In general, Satan has been read as a queer, subversive figure, an icon for anyone looking to reject good and evil binaries (and binaries at large).

By the 1970s, satanic feminism, witchcraft, and other forms of occultism began to have a renaissance in America. Old Pagan goddesses like Nyx and Wiccan figures like Hekate began to replace traditional deities. In particular, Wiccan faiths grew popular and easily accessible, as books of rituals publicized ideas that had previously been known only in esoteric circles. Movies like The Wicker Man and books like Starhawk’s The Spiral Dance publicized Pagan occultism and the West Coast’s ecological feminism, synthesizing them into an appealing blend of radicalism and spirituality. At the end of the 20th century, writers like Gloria Anzaldúa (Borderlands/La Frontera), and Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estes (Women Who Run With the Wolves) proposed a new kind of healing through occultism, ritual, and writing and ritual that shattered binaries, linearity, and body politics.

Today in 2020, occultism has been reappearing with a vengeance. Topics like astrology, tarot, and political, progressive interpretations of them have never been more popular, finding a home with everyone from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (who has been called a witch by some conservatives) to Lana Del Rey and teens on TikTok.

Lana Del Rey Confirms She Used Witchcraft Against President Trump | Billboard News

www.youtube.com

Modern occultism is often deeply political, a way of merging anger at established systems with spirituality, community, and internal work. Some argue that these rituals are shaping the sort of meaning and healing that people, particularly women, have been seeking. “In the absence of effective, socially enforced structures by which abusers can face justice for their actions, rituals and ritual behavior take on a vital spiritual, psychological, and social role for survivors,” writes Vox. “They foster community and solidarity. They enable the processing of trauma.”

Considering the general state of affairs right now, it’s inevitable that people would be turning to spirituality in order to foster solidarity and connection in an ever-more scattered world.

Trauma is by definition a kind of blockage, a darkness that cannot be surmounted. In this way, acknowledging trauma and personal darkness, rage, and taboo emotions through witchcraft and occultism is similar to psychoanalysis in that it forces these grievances into the light, and potentially liberates them. Though women aren’t typically burned at the stake for being witches anymore, violence against women is a tremendous and deadly problem, and things are much worse for poor women and women of color.

Still, none of this is to say that witchcraft is an all-encompassing solution or a healing force on its own. If anything, it’s a way of coming to terms with brokenness and accepting the damages that come with being alive; it couldn’t be healing without systemic and structural changes.

The Problems and Future of Occultism and Feminism

So back to the original question: Is what happens at the end of the film The Witch a feminist victory? Could we say that as she rises into the air, Thomasin is dealing with her trauma, becoming a better version of herself?

In spite of everything, I’m not sure we can. The truth is, by the end of the film, Thomasin had no other choice—and neither did many women who defected to witchcraft. Often, they needed these communities to literally survive; they had no option to return to the garden. The archetype of the witch woman is shaped in order to exist in opposition to patriarchal structures and the pain they cause; in that, it still defers to the patriarchy in some way, and it’s still shaped by and around trauma. This isn’t the case for all occultism, but still.

In an ideal form, occultism and the shattering it involves would evolve towards redemption and towards the creation of a better world outside of oppressive structures, one where people would be free to live as they choose from the get-go, not just when everything falls to pieces. And to be redemptive, these theories must be taken further, outside of just a focus on gender and into a focus on race and class. Ideally, occultism wouldn’t only deconstruct and defect; it would would evolve towards the creation of something else.

Liberalism and Feminism Were Born From the Occult

www.youtube.com

73

73